Number of Spencers Purchased

Types of Spencers

Three general classes of arms exist that were made

Early Spencer Models Spencer’s first gun patent of March 6, , No.

Certainly by the end of , Spencer had built his

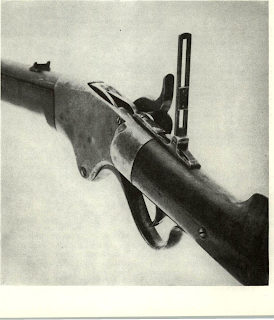

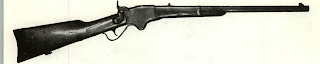

Small frame Hartford-made Spencer carbine cal. .44RF has Lawrence sight of type fitted to Sharps guns; reveals Sharps

suggest there is a sequence of design, judging from the

All had side back-action locks and side hammers manually cocked for each shot. Sporting rifles and military

The .44’s and .36’s are the earliest arms of the

ing a day’s supply of shots without the need for flask

Spencer Finds a Factory

Cheney had lived next door in Hartford to Gideon

With Spencer, it was a different story. Cheney introduced Spencer to Welles and a test of the new gun was

The mechanism is compact and strong. The piece was fired

Government Contracts

Frank Cheney and Christopher Spencer went to Boston to supervise the manufacture of these first Navy

Though the Navy required but 700 rifles, apparently

According to Special Order No. 311, Major General

Spencer Company agent Warren Fisher got after the

Following the November 22, tests, Spencer was

Washington, December 18,

Your obedient servant

One of the proprietors of the Spencer repeating rifle

Secretary of War

Ordnance General Ripley is always held up as the

Cameron was a political appointee, given the post

Ordnance Office

Respectfully, your obedient servant

James W. Ripley,

Brigadier General

To

Warren Fisher, Jr., Esqr.

Boston, Massachusetts

Fisher returned to Boston and, receiving the Ripley

Upon their appeal to all parties to furnish them with

When on January 29 Stanton ordered copies of contracts from the contractors, Fisher prepared his and

On February 24 he went to Washington to deliver the

Finding that deliveries scheduled for March, April,

The Navy order was ready for shipping by December 25, , packed in chests of ten guns each, plus sword bayonets, brushes, cleaning rods, and screw drivers.

These rifles were ultimately issued to the Mississippi

By the end of December, the rifles for the Army

Spencers Used in the War General Norton in (American Breechloading

Production of parts was speeding up and rifles were

Grant himself could not order the purchase of any

Captain G. M. Barber, Ohio Sharpshooters, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, May 19, , noted: “I have

Standard Spencer carbine was made by Boston firm in old Chickering Piano Factory building, had improved Lawrence rear

been drilling my battalion together with some companies of the 10th Ohio Infantry, in target practice for

Specimen carbines were also distributed to officers

At Norfolk, Virginia, where General King’s regiment

The man who did the most to spread the fame of the

And at the “Metallic Cartridge Manufactory” of

So durable an arm was Wilder’s second choice, and

During April or May, , Wilder’s Brigade received its issue of Spencer rifles. These were not

Spencer, during his sojourn in Hartford with Colt, had

The Spencer in Battle

In the Army of the Potomac it is equally well known. The

As Pleasonton’s cavalry unpleasantly pursued the

An unknown chronicler who addressed a report on

After the battle at Gettysburg whilst our cavalry were

One day as our line of skirmishers was advancing, one of

A hopeful editorial appearing about this time in

Repeater dubbed “horizontal shot tower” was adopted as

annihilation of one or both of the contending parties,

Apparently at least one Rebel soldier held to this

There is a fascinating legend attached to this inter-

There is some truth to this story. Spencer did see

a source document as C. M. Spencer’s own words

On the 18th of August, , I arrived at the White House

Here was no sudden secret interview; Lincoln was

Spencer continues:

Arriving at the appointed time, I found all in readiness

While we were waiting for Robert, Mr. Lincoln discovered

Arriving at the shooting ground, Mr. Lincoln, looking down

The end of the board which the President had shot at was

The following evening Lincoln, having retained the

loading with absolutely contemptible simplicity and ease

Hay reports the trio had some kibitzers absolutely

I have met shooting experts of this type in my own

The target board at which Lincoln fired, that was

Discovering this lost shingle would be a most interesting thing for collectors, as it might identify beyond

Source for most Spencer sporting rifle information is

Bore measurement over lands...........443"

Number of grooves....................................6

Length of barrel, muzzle: chamber front . 24%"

Length of barrel to rear of chamber..........26"

Length of chamber....................................3A"

Chamber at rear, diameter of %" part .. . .56"

Chamber at front, diameter of 3A" part . . .443"

Receiver marked on top in three lines with:

RIFLE CO. BOSTON, MASS.

PATd MARCH 6,

With what kind of rifle did Lincoln fire at the wood

“. . . I took the rifle from its case and presented it to

My opinion is, in view of Lincoln asking Spencer

Special Spencer sporting rear sight

on the first 10,000 order of .56-.56 rifles for the Army;

Checking into the differences between the sporting

one of the first Spencer had made on the .56-.56 production line. If so, could he have chosen No. 7 as his

On Saturday, September 19, , Van Cleve’s and

As the rebels entered this field, in heavy masses fully exposed, the mounted infantry, with their seven-shooting Spencer

When the firing ceased, one could have walked for two

While Wilder did not claim that his brigade defeated

A special cartridge box was invented by Blakeslee

Michigan forces became famous with their Spencers.

of the swivel-fastened ordinary sling or, in more alert

Headquarters Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac

Mr. F. Cheney

Dear Sir:—Being in command of a Brigade of Cavalry

Very respectfully &c.

G. A. Custer,

Brigadier General

In June, the general of the flowing locks got a chance

New York Herald, June 2nd,

Torbert’s Division.

As the fight waxed hottest, between two and three o’clock,

The Confederate estimation of the Spencer was quite

The captures which we have made from the enemy embrace

Resplendent in “Jeff Davis” cap and shoulder scales, sergeant

Pair of Boston Spencers owned

This wholly gratuitous piece of scribbling did nothing to cheer up harassed and much-overworked General J. G. Rains, CSA. As superintendent of the Confederate powder mill at Augusta and Chief of the Nitre

The repeaters lent an aura of invincibility to the

The Spencer did not win the War; on the other hand

, for 35,000 Spencer carbines. The Tremont

MARCH 6, /MANUFD AT PROV. R. I. BY BURNSIDE

The last use of a Spencer carbine in anger was by a

There is a recent and possibly well founded belief

some have it. Ironically, the weapons which Booth

The corollary incident looms less bright in history,

In the Model a peaceful note was intruded into the mechanism. Quaker inventor Edward M. Stabler

Christopher Miner Spencer died in . His work

Types of Spencers

Three general classes of arms exist that were made

Early Spencer Models Spencer’s first gun patent of March 6, , No.

Certainly by the end of , Spencer had built his

Small frame Hartford-made Spencer carbine cal. .44RF has Lawrence sight of type fitted to Sharps guns; reveals Sharps

suggest there is a sequence of design, judging from the

All had side back-action locks and side hammers manually cocked for each shot. Sporting rifles and military

The .44’s and .36’s are the earliest arms of the

ing a day’s supply of shots without the need for flask

Spencer Finds a Factory

Cheney had lived next door in Hartford to Gideon

With Spencer, it was a different story. Cheney introduced Spencer to Welles and a test of the new gun was

The mechanism is compact and strong. The piece was fired

Government Contracts

Frank Cheney and Christopher Spencer went to Boston to supervise the manufacture of these first Navy

Though the Navy required but 700 rifles, apparently

According to Special Order No. 311, Major General

Spencer Company agent Warren Fisher got after the

Following the November 22, tests, Spencer was

Washington, December 18,

Your obedient servant

One of the proprietors of the Spencer repeating rifle

Secretary of War

Ordnance General Ripley is always held up as the

Cameron was a political appointee, given the post

Ordnance Office

Respectfully, your obedient servant

James W. Ripley,

Brigadier General

To

Warren Fisher, Jr., Esqr.

Boston, Massachusetts

Fisher returned to Boston and, receiving the Ripley

Upon their appeal to all parties to furnish them with

When on January 29 Stanton ordered copies of contracts from the contractors, Fisher prepared his and

On February 24 he went to Washington to deliver the

Finding that deliveries scheduled for March, April,

The Navy order was ready for shipping by December 25, , packed in chests of ten guns each, plus sword bayonets, brushes, cleaning rods, and screw drivers.

These rifles were ultimately issued to the Mississippi

By the end of December, the rifles for the Army

Spencers Used in the War General Norton in (American Breechloading

Production of parts was speeding up and rifles were

Grant himself could not order the purchase of any

Captain G. M. Barber, Ohio Sharpshooters, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, May 19, , noted: “I have

Standard Spencer carbine was made by Boston firm in old Chickering Piano Factory building, had improved Lawrence rear

been drilling my battalion together with some companies of the 10th Ohio Infantry, in target practice for

Specimen carbines were also distributed to officers

At Norfolk, Virginia, where General King’s regiment

The man who did the most to spread the fame of the

And at the “Metallic Cartridge Manufactory” of

So durable an arm was Wilder’s second choice, and

During April or May, , Wilder’s Brigade received its issue of Spencer rifles. These were not

Spencer, during his sojourn in Hartford with Colt, had

The Spencer in Battle

In the Army of the Potomac it is equally well known. The

As Pleasonton’s cavalry unpleasantly pursued the

An unknown chronicler who addressed a report on

After the battle at Gettysburg whilst our cavalry were

One day as our line of skirmishers was advancing, one of

A hopeful editorial appearing about this time in

Repeater dubbed “horizontal shot tower” was adopted as

annihilation of one or both of the contending parties,

Apparently at least one Rebel soldier held to this

|

| Repeater dubbed "horizontal shot tower" was adopted as corps insignia by cavalryman Wilson |

Spencer Sees Lincoln

With such a battle record, Spencer decided to againThere is a fascinating legend attached to this inter-

There is some truth to this story. Spencer did see

a source document as C. M. Spencer’s own words

On the 18th of August, , I arrived at the White House

Here was no sudden secret interview; Lincoln was

Spencer continues:

Arriving at the appointed time, I found all in readiness

While we were waiting for Robert, Mr. Lincoln discovered

Arriving at the shooting ground, Mr. Lincoln, looking down

The end of the board which the President had shot at was

The following evening Lincoln, having retained the

loading with absolutely contemptible simplicity and ease

Hay reports the trio had some kibitzers absolutely

I have met shooting experts of this type in my own

The target board at which Lincoln fired, that was

Discovering this lost shingle would be a most interesting thing for collectors, as it might identify beyond

Source for most Spencer sporting rifle information is

Bore measurement over lands...........443"

Number of grooves....................................6

Length of barrel, muzzle: chamber front . 24%"

Length of barrel to rear of chamber..........26"

Length of chamber....................................3A"

Chamber at rear, diameter of %" part .. . .56"

Chamber at front, diameter of 3A" part . . .443"

Receiver marked on top in three lines with:

RIFLE CO. BOSTON, MASS.

PATd MARCH 6,

With what kind of rifle did Lincoln fire at the wood

“. . . I took the rifle from its case and presented it to

My opinion is, in view of Lincoln asking Spencer

Special Spencer sporting rear sight

on the first 10,000 order of .56-.56 rifles for the Army;

Checking into the differences between the sporting

one of the first Spencer had made on the .56-.56 production line. If so, could he have chosen No. 7 as his

Other Evidence Favoring the Spencer

The heavy casualties at Chickamauga had sealedOn Saturday, September 19, , Van Cleve’s and

As the rebels entered this field, in heavy masses fully exposed, the mounted infantry, with their seven-shooting Spencer

When the firing ceased, one could have walked for two

While Wilder did not claim that his brigade defeated

Results of the Interview with Lincoln

The result of Spencer’s interview had been characterized as a highly successful one, and after that it is saidThe Model Adopted

The model adopted for the cavalry was 22 inchesA special cartridge box was invented by Blakeslee

Michigan forces became famous with their Spencers.

of the swivel-fastened ordinary sling or, in more alert

Headquarters Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac

Mr. F. Cheney

Dear Sir:—Being in command of a Brigade of Cavalry

Very respectfully &c.

G. A. Custer,

Brigadier General

In June, the general of the flowing locks got a chance

New York Herald, June 2nd,

Torbert’s Division.

As the fight waxed hottest, between two and three o’clock,

The Confederate estimation of the Spencer was quite

The captures which we have made from the enemy embrace

Resplendent in “Jeff Davis” cap and shoulder scales, sergeant

Pair of Boston Spencers owned

This wholly gratuitous piece of scribbling did nothing to cheer up harassed and much-overworked General J. G. Rains, CSA. As superintendent of the Confederate powder mill at Augusta and Chief of the Nitre

Influence on Tactics

The issue of breechloaders like the Spencer gaveThe repeaters lent an aura of invincibility to the

The Spencer did not win the War; on the other hand

, for 35,000 Spencer carbines. The Tremont

MARCH 6, /MANUFD AT PROV. R. I. BY BURNSIDE

The last use of a Spencer carbine in anger was by a

There is a recent and possibly well founded belief

some have it. Ironically, the weapons which Booth

The corollary incident looms less bright in history,

In the Model a peaceful note was intruded into the mechanism. Quaker inventor Edward M. Stabler

After the War

The denouement of Spencer and his rifle story cameChristopher Miner Spencer died in . His work

Comments

Post a Comment