When Ripley gave Eli Remington II the contract for 10.000 rifles with sword bayonets he set in motion the

50.000 or 100,000 Springfields in addition to their

Remington stated that he desired to commit his fac

With this sort of hard bargaining in cash terms star

OFFICE OF REMINGTON’S ARMORY

We are, very respectfully, your obedient servants,

E. REMINGTON & SONS

Though Eliphalet Remington III penned the letter,

The contracts given were confirmed, and the Reming

Contract

13 June

5.000 Navy revolvers cal. 36

13 June

20.000 Army revolvers cal.

11 August

6 July

$12.

Delivered

4,000 (plus 8,251)

12,505 (5,102; 14,402)

March 31, —June 22,

10,001—April 18, —

January 8,

13,908—July 8, —No

21 November

64,900 army revolvers cal.

13 December

2,500

14 December

40.000 Springfield rifle mus

24 October

15.000 Remington breech

24 October

20.000 Army revolvers cal.

62,003—November 23,

2,500

40.000—May 31, —May

15.000—September 30,

20,000— January 12, —

To final payments in May of for arms con

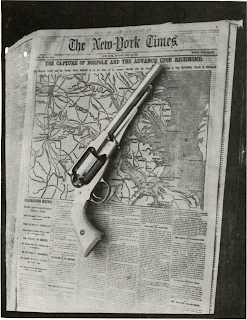

Of 12,251 Navy revolvers delivered and paid for,

arm was budgeted for the labor of Government in

Possibly as many as 5,100 of the first or

and on the barrel flat at that point; also on the cylinder

,

as it is usually stamped along the barrel top

Beals joined the lever to the base pin; it was held in

These big pistols were heralded to the trade as

A sale to the State of South Carolina of 1,000 Rem

The Elliott lever was more symmetrical in form, not

The pin that could be withdrawn without dropping

Details distinguishing between these three types and

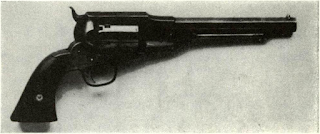

Beals MI 858

Front sight: dovetail, brass or German silver cone.

Frame, solid, shrouds barrel threads completely.

Loading lever: Square at back end with web of streamline

Cylinder: Smooth, no safety notches, nipple cuts narrow as

Calibers: .36 and .44.

Barrel: Octagon, 8-inch in Army, 7‘/i-inch in Navy. Marked

Front sight: dovetail, brass or German silver cone.

Frame: Solid, transitional, may expose threads of barrel

Loading lever: Web runs forward to reenforce beneath

Cylinder: Smooth; no safety notches.

Calibers: .36 and .44.

Barrel: Octagon, 8-inch in Army, 7V4-inch in Navy. Marked:

New Model

Front sight: Iron blade cut by scooping sides of a cylindrical

Frame: Solid, does not shroud barrel threads.

Loading lever: Must be dropped to pull T-head cylinder

Cylinder: Smooth. Safety notch between each chamber for

Calibers: .36 and .44.

Barrel: Octagon, 8-inch in Army, 7‘/2-inch in Navy (some

While the detail differences noted above caused

frame. Not patentable, these simplicities greatly reduced

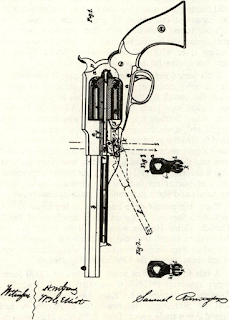

In its perfected form the rolling block system ap

Geiger’s breech system had a hinged block that swung

. Chambered for the .56-.50 Spencer rimfire

Remington’s War Contribution

First came the famous Zouave rifles. Though most

with foreign arms or transformed Springfields, the title

More important were the 40,000 Springfields. In

In spite of Hagner’s haggling over the values of

Now, a great corporation had emerged from the fires

During the war, production of 3,000 revolvers a

Junior,was the

sadded to

& Son.

Remington War Contracts

50.000 or 100,000 Springfields in addition to their

they are working zealously and extrahours to expedite their work.

Remington stated that he desired to commit his fac

With this sort of hard bargaining in cash terms star

OFFICE OF REMINGTON’S ARMORY

We are, very respectfully, your obedient servants,

E. REMINGTON & SONS

Though Eliphalet Remington III penned the letter,

The contracts given were confirmed, and the Reming

poundmasterof Ilion. Possibly Henry H.

Contract

13 June

5.000 Navy revolvers cal. 36

13 June

20.000 Army revolvers cal.

after a patternto be deposited.

11 August

Harpers Ferryrifles

6 July

All the army .44 revolversthey can deliver within the present year (i. e., until December 31, ) @

$12.

Delivered

4,000 (plus 8,251)

12,505 (5,102; 14,402)

March 31, —June 22,

10,001—April 18, —

January 8,

13,908—July 8, —No

21 November

64,900 army revolvers cal.

13 December

2,500

Harper’s Ferryrifles

14 December

40.000 Springfield rifle mus

24 October

15.000 Remington breech

24 October

20.000 Army revolvers cal.

62,003—November 23,

2,500

40.000—May 31, —May

15.000—September 30,

20,000— January 12, —

To final payments in May of for arms con

Of 12,251 Navy revolvers delivered and paid for,

arm was budgeted for the labor of Government in

Possibly as many as 5,100 of the first or

BealsArmy .44’s were delivered; 4,250 at $12 onModel

and on the barrel flat at that point; also on the cylinder

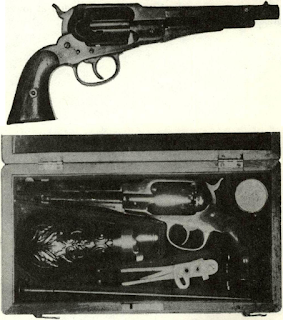

Four Basic Remington Handguns

Collectors confuse terminology slightly because ofNew Model; in all, six distinctly different

Beals Patent September 14,

,

as it is usually stamped along the barrel top

Beals joined the lever to the base pin; it was held in

These big pistols were heralded to the trade as

Ain a brochure of .New And Superior Revolver

all he could get forthey did not catch on commerciallythe western army

A sale to the State of South Carolina of 1,000 Rem

BealsRemington informed Judge Holt they had,44(?).

5,000 rifles for the State of MisMeanwhile, the Beals loading lever in production on the big solid frame .36 and .44 revolverssissippi, in November, . . . was also peremptorily declined.

The Elliott lever was more symmetrical in form, not

|

| Beals type pistol is distinguished by frame covering back |

New Modelpattern.

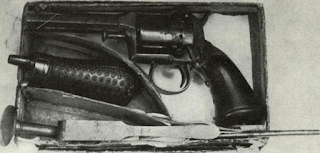

The pin that could be withdrawn without dropping

Details distinguishing between these three types and

Beals MI 858

Front sight: dovetail, brass or German silver cone.

Frame, solid, shrouds barrel threads completely.

Loading lever: Square at back end with web of streamline

Cylinder: Smooth, no safety notches, nipple cuts narrow as

Calibers: .36 and .44.

Barrel: Octagon, 8-inch in Army, 7‘/i-inch in Navy. Marked

Front sight: dovetail, brass or German silver cone.

Frame: Solid, transitional, may expose threads of barrel

Loading lever: Web runs forward to reenforce beneath

Cylinder: Smooth; no safety notches.

Calibers: .36 and .44.

Barrel: Octagon, 8-inch in Army, 7V4-inch in Navy. Marked:

New Model

Front sight: Iron blade cut by scooping sides of a cylindrical

Frame: Solid, does not shroud barrel threads.

Loading lever: Must be dropped to pull T-head cylinder

Cylinder: Smooth. Safety notch between each chamber for

Calibers: .36 and .44.

Barrel: Octagon, 8-inch in Army, 7‘/2-inch in Navy (some

While the detail differences noted above caused

modemhandgun at a less price.

frame. Not patentable, these simplicities greatly reduced

Geiger’s Rolling Block

While Beals had his brief day at Remington, andlate flintlock period,say . Con

In its perfected form the rolling block system ap

Geiger’s breech system had a hinged block that swung

split breech Remington.It was this pattern of breech

. Chambered for the .56-.50 Spencer rimfire

Remington’s War Contribution

Remand the Springfields at $17, that Remingington rifle

First came the famous Zouave rifles. Though most

New Modelcharacteristics. First issue had fluted

with foreign arms or transformed Springfields, the title

Zouave riflehas clung to this special weapon. It is

Chasseurs de Vincennes

More important were the 40,000 Springfields. In

In spite of Hagner’s haggling over the values of

Now, a great corporation had emerged from the fires

During the war, production of 3,000 revolvers a

Comments

Post a Comment