Instead, the Requa guns, five in all, purchased at a

geant of the 25th South Carolina Infantry, then in Fort

Whether the Confederates ever used such a gun is

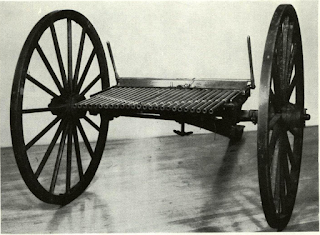

These curious piano-hinge organs whose song was

24, , at $40 per 100, a reduction in price of $10

per hundred. Five guns at $1,000 each were received

geant of the 25th South Carolina Infantry, then in Fort

Whether the Confederates ever used such a gun is

These curious piano-hinge organs whose song was

24, , at $40 per 100, a reduction in price of $10

per hundred. Five guns at $1,000 each were received

Comments

Post a Comment