Almost unrecorded is the important part which a

these was a shipment of Manhattan revolvers and am

Governor Oliver P. Morton was frantically sending

Anthony retained two pistols and 400 cartridges pre

While these pistols of Manhattan make were tech

In order to obtain redress of this loss, for the pistols

The money in question did not total millions, but it

the prices charged are reasonable, and they therefore

Boker had apparendy wanted to secure an agency

Beginning in , Manhattan moved their office to

The top of the cylinder stop release also served as

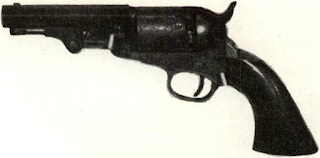

Variations of early production are noted; a first type

other minor engineering changes can be traced through

White and Smith & Wesson sued Boker under the

A permanent stop order was issued by Chief Justice

The use of the intermediate recesses, r r, in combination

The artist however did not show the double stops

More important in their scheme of business was

Arnold sought to buy from Colt’s a drop hammer of

Says Smith in conclusion, but slightly in error,

London Pistol Company which succeeded Colt.

Smith makes a fundamental error in considering that

The stopping of the engines at Thames Bank did not

That London fabricated parts were returned to Hart

Given this fact we must return to the observed great

for the absence of this name in all listings of

Colt could not by snapping his fingers cause the dis

Why this name was used is puzzled over by Nutter.

War did not bring to Manhattan the unmitigated flow of profits that some fabricants enjoyed. During the

List of machinery ready to be turned over by the

6 milling machines

3 four-spindle drill presses, finished

1 rifling machine

2 edging machines, finished

4 screw and cone machines, ready April 1,

6 plain engine lathes, ready April 20,

4 drilling lathes, ready April 20,

3 edging machines, ready April 20,

3 screw and cone machines, ready May 1,

1 quadruple drop (four drops) ready May 1,

4 cone lathes for drilling cones, ready April 20,

New York, March 24,

The above tabulation clearly indicates Manhattan

A second list

company known as The American Standard Tool Com

Western agent Ben Kittredge of Cincinnati, Ohio,

Some of these later .36 caliber Manhattans were sold

I found myself in a hotel nearby with several doctors

It was when the great commander was

A pistol possibly having a little more active career

copiesof

secondin that they are the size mostary U. S. martial pistols,

Confiscated Arms

these was a shipment of Manhattan revolvers and am

Governor Oliver P. Morton was frantically sending

all revolvers in his hands not absolutelyneeded for effective discharge of office duties.

Anthony retained two pistols and 400 cartridges pre

office dutiesand delivered to Governor

Facts have come to my knowledge which satisfyreported the Unitedme beyond all doubt that this box of pistols was never intended for Rebel use, the owners being loyal; and this box was a sample which this agent was using in effecting sales to Union men,

I therefore unhesitatingly state that the amount realizedby the governor ought, in justice to the claimant and owner, to be paid, as the pistols received in exchange are now in the service of the United States.

While these pistols of Manhattan make were tech

military pistolsby reason of circumstance,

Shortly after they were received, I exchanged them forNavy revolvers, now in the service of the United States,

In order to obtain redress of this loss, for the pistols

The money in question did not total millions, but it

By direction of the Secretary of War the reports infuture are to be addressed to the chief of ordnance for execution, without reference to the War Department.

the prices charged are reasonable, and they therefore

Imitations of a Smith & Wesson

These little pistols, the only ones which can layBoker had apparendy wanted to secure an agency

bigcompanies of the time, for United

hurting

We suspect that Boker was influsays Nutter.ential in the initial decision to manufacture the .22 caliber revolvers,

Beginning in , Manhattan moved their office to

suspectsomething: that prior to the

Manhattan,and purposely left the tops of

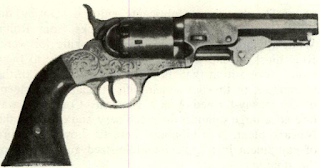

Decorative engravingnotesstands out as one of the distinctive characteristics of Manhattan’s First Model .22 caliber revolvers,

The vertical flats of the barrelswere hand engraved with a scroll design . . . Barrels were usually finished blue, occasionally were silver plated; the seven-shot cylinders, s/s inches in length, were not engraved, had only one cylinder stop per chamber, with no provision for safety rests and were finished blue. The cylinder stop (in the frame top strap) has a nose which is set at an angle to the nose on the hammer, so that cocking the latter raises the former (lifting the locking stud out of the cylinder notch), but, in firing, the two noses pass one another.

The top of the cylinder stop release also served as

Variations of early production are noted; a first type

other minor engineering changes can be traced through

A Second Model

A second model .22 having a distinctive flat frame ofWhite and Smith & Wesson sued Boker under the

All consisted of extended chambers through the rear of the cylinder for the purpose of loading them at the breech from behind, either by hand or by self-acting chargers from a magazine placed in the rear of said cylinder.

A permanent stop order was issued by Chief Justice

Made for Smith &No Manhattan gun is known with this mark,Wesson.

Other Business

An aura of immunity in some respects surroundedThe use of the intermediate recesses, r r, in combination

The artist however did not show the double stops

More important in their scheme of business was

General Superintendent of the Manhattan Comas he testified in the casepany’s mechanical business,

Arnold sought to buy from Colt’s a drop hammer of

London Pistolswere Manhattans Briefly, collectors had long noticed the existence of a

London Pistol Company.It was not

Patented Dec. 27, .When Sam Smith

London Pistolguns were at last recognized as being AmeriCompany

A History of Firearms(p. 135) that:

Colt’s invasion (of the British gun trade) was not a success, and the London factory was closed in . The relics were taken over, and a small company appears to have used up the surplus of parts, as The London Pistol Company, a name I have seen impressed over an al most obliterated London Colt stamp.

Says Smith in conclusion, but slightly in error,

Ibelieve we may judge from that that the true English London Pistol Company product is one of leftover Colt parts and that few were manufactured. It is significant that J. N. George’s book, English Pistols and Revolvers, the best book on that subject, makes no mention of the

London Pistol Company which succeeded Colt.

Smith makes a fundamental error in considering that

succeededColt’s closing down of the London

The stopping of the engines at Thames Bank did not

That London fabricated parts were returned to Hart

London’ is all but obscured by a blob of fused brasstrigger guard. The barrel is finished through the filed stage, rifled; and the bore, except for scale, is perfect. That it is not a second hand barrel returned for some cause is revealed by the absence of the front sight pin; instead, the hole for the sight is perfectly clean. If there had been a pin, in spite of the molten heat, the brass of the sight would have remained smeared at the front sight hole. This is an unfinished London Colt barrel, from storage in the parts wareroom at Hartford in .

Given this fact we must return to the observed great

for the absence of this name in all listings of

impressed over an almost obliteratedIt may be that this is the shape ofLondon Colt stamp.

Colt could not by snapping his fingers cause the dis

over an almost obliterated London Colt stamp.

Why this name was used is puzzled over by Nutter.

London makethrough linking them always

coldand that they were dumped on the Northernwar,

estimate that only a very fewThis would seem to lendhundred were so marked.

War did not bring to Manhattan the unmitigated flow of profits that some fabricants enjoyed. During the

List of machinery ready to be turned over by the

6 milling machines

3 four-spindle drill presses, finished

1 rifling machine

2 edging machines, finished

4 screw and cone machines, ready April 1,

6 plain engine lathes, ready April 20,

4 drilling lathes, ready April 20,

3 edging machines, ready April 20,

3 screw and cone machines, ready May 1,

1 quadruple drop (four drops) ready May 1,

4 cone lathes for drilling cones, ready April 20,

New York, March 24,

The above tabulation clearly indicates Manhattan

mechanical businessaffairs the

edging machine

A second list

of machinery in the pistol factory ofincluded non-specializedthe Manhattan Arms Company ready for use by the Union Firearms Company

All small tools and a large amount of vacantIt would seem that Judge Taney’s order severelyroom.

Late Manhattan Pistols

company known as The American Standard Tool Com

Western agent Ben Kittredge of Cincinnati, Ohio,

between the cock and theThenipple to throw the fire laterally from the nipple.

Some of these later .36 caliber Manhattans were sold

During this visit,Grant wrote in his Memoirs,

Ireviewed Banks’ army a short distance above Carrolton. The horse I rode was vicious and but little used, and on my return to New Orleans ran away and, shying at a locomotive in the street, fell, probably on me. I was rendered insensible, and when I regained consciousness

I found myself in a hotel nearby with several doctors

It was when the great commander was

Grant’s Own.

A pistol possibly having a little more active career

Comments

Post a Comment