The little smithy at Ilion Gulph by had grown

mon in all countries. Instead of the barrel being hit

Existing descriptions of barrel manufacture during

At Remington other work was in progress to have

These rifles are to be .58 inch calibre, and to have a three

The order was acknowledged and agreed to, at

The rifle design established used a stock of Ml855

order filled were rifled with 5 grooves. The lock is

New Remington Army Model .44 Revolver

ORDNANCE OFFICE

Remington accepted the order by J. Remington in

Remington Background

Another rifle often pictured as Remington’s first is shown

lishment in the upper Mohawk Valley, much as the

Among many things not clear are a few certain

Long Rifles, New York was the trade center to which

A most interesting account appears in The Reming

The narrative first recites the story of a young man

What actually happened is subject to conjecture,

sentiment at the close of the War of to

The First Remington Rifle

verted fake. More probably a

Pill-lock Rifles

Pill lock ignition with striker on side of lock is found on some New York State rifles like this handsome Albany rifle of

Billinghurst of Rochester, New York, made a number

In Remington made his first rifle barrel. Alden

The job was done at last. Lite had a tightly wound spiral of

In addition to confusing the fabrication of a

A commercial success it was; idyllic essays on

The date of coincided with a move by the

Tradition continues to note that Remington got

But business continued, and Remington looked upon

We are informed by The Remington Centennial

By Remington had matured considerably in

Sidehammer plain sporting rifles, with full stocks

At Chicopee Falls, in Massachusetts, (Eli Remington)

mechanism. With his inventor’s perception, he saw that he

Jenks was a Yankee, of Welsh descent, with curly hair, round

The upshot of Remington’s visit to Chicopee Falls was that

Hatch concludes this passage by noting that there

But these are not the only catches in the Hatch

ricating the novel Model U. S. Navy pistol or

Such philanthropy seldom paid oft’, but the type

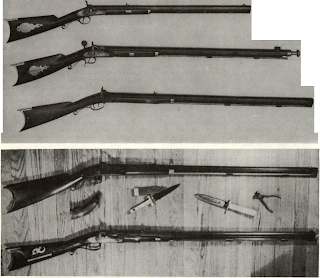

The smallest size is a buggy rifle or possibly a boy’s

Next in size would be described as the Basic Sporter.

The cognomen

stance comes to mind of traditional maker or parts

Among possible suppliers of locks marked

To the stock and lock, Remington fitted a barrel

This same basic sidelock rifle can be found in a

The plainest form of this rifle has only a brass butt

This arm gives evidence of its Remington origins

This handsome rifle has seen better days but still

Among little details of outline and shaping which

Remington Arms was soon to fill a large role in the

The fact is that E. Remington & Sons from the time

The

recalled is about .50-inch, not exceptionally large. It

Any gunmaker worth his salt could slave over spoke

maker’s mark,it may be seen that Remington could

Barrel Straightening

mon in all countries. Instead of the barrel being hit

Existing descriptions of barrel manufacture during

At Remington other work was in progress to have

|

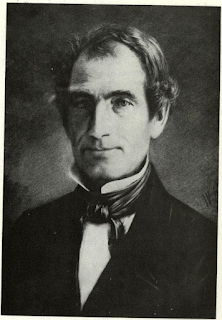

| Eli Remington, Jr., as a lad built a rifle at Ilion Gulph which was first firearm in series of possibly 30,000,000 made to date. Gun's ignition type has remained puzzle for modern researchers |

Remington Zouave Rifle

One of the most colorful of Civil War arms is theRemington Zouave rifle,caliber .58. The

regulation rifles with sword bayonets,the article pro

These rifles are to be .58 inch calibre, and to have a three

The order was acknowledged and agreed to, at

The rifle design established used a stock of Ml855

order filled were rifled with 5 grooves. The lock is

heretofore made by you for government,as Ripley

BealsNavy re

I am procuring all of them I can for the westernHagner told Ripley,army,

and hope to hear I canget all I may need. I have seen no revolver I like as well, and the price is nearer the cost than some others.

New Remington Army Model .44 Revolver

ORDNANCE OFFICE

Remington accepted the order by J. Remington in

Remington Background

Another rifle often pictured as Remington’s first is shown

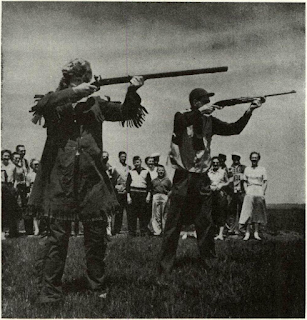

competitionwith modern Remington .280

Dan’l Boonecharacter is a fraud, having a Common

lishment in the upper Mohawk Valley, much as the

Among many things not clear are a few certain

Liteexcelled

Long Rifles, New York was the trade center to which

long fowlers.By that date the United

A most interesting account appears in The Reming

The narrative first recites the story of a young man

a youngA footnote in this typescript refers to theman residing in Litchfield whose inclinations pressed him in the same direction as the young man already spoken of.

What actually happened is subject to conjecture,

sentiment at the close of the War of to

buyYouthful Lite Remington’s patriotic ardorAmerican.

The First Remington Rifle

buckhornsight and blade

recon

verted fake. More probably a

firstis another rifle

The First Remington Rifle.This arm has a shad

Pill-lock Rifles

Pill lock ignition with striker on side of lock is found on some New York State rifles like this handsome Albany rifle of

Billinghurst of Rochester, New York, made a number

Remington’s First Barrels

In the Remington story, certain dates are significant.In Remington made his first rifle barrel. Alden

The job was done at last. Lite had a tightly wound spiral of

jumping.It jarred the malleable edges of the spiral

In addition to confusing the fabrication of a

old handsat Remington Arms by describing a

A commercial success it was; idyllic essays on

The spring and other parts wantthe business that emergeding he made himself,

The date of coincided with a move by the

Tradition continues to note that Remington got

But business continued, and Remington looked upon

The First Factory

Factory it was, this stone foundation mill with twoAThe elusivebig tilt hammer, several trip hammers, boring and ri fling machines, grindstones, and so on.

and so onwe hope has damned this

We are informed by The Remington Centennial

The lapwelded barrel was standard untilNo claim can be made that Remington in, and he got together a battery of trip hammers for forging and welding his barrels. Finer dimensions became a factor in his business when the output grew large enough to warrant carrying a stock of spare parts for his customers, and so he improved those parts in ways that gave at least the beginnings of interchange ability.

the barrel maker in Litchfield.While

By Remington had matured considerably in

Jenks Carbine

The Navy’s breech-loading carbine designed bySidehammer plain sporting rifles, with full stocks

At Chicopee Falls, in Massachusetts, (Eli Remington)

mechanism. With his inventor’s perception, he saw that he

Jenks was a Yankee, of Welsh descent, with curly hair, round

The upshot of Remington’s visit to Chicopee Falls was that

Hatch concludes this passage by noting that there

hurry-up order of ancient flintlocks—the lastLike the Unicornever issued to American troops!

But these are not the only catches in the Hatch

galvanizedkind, he coming from South

best breechloader ever,

ricating the novel Model U. S. Navy pistol or

boxlock pistol.Perhaps Remington had gotten the

Such philanthropy seldom paid oft’, but the type

Sporting Rifles

Remington continued production of common AmeriThe smallest size is a buggy rifle or possibly a boy’s

Next in size would be described as the Basic Sporter.

B. FA Coare placed

The cognomen

X Fire Arms Co.was not too

|

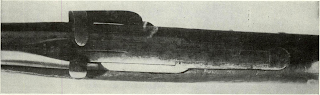

| Long strip on top of Jenks carbine lifts up by hook thumbpiece to uncover trough for loading combustible cartridge. |

flyto guide the sear out

Among possible suppliers of locks marked

B. FAwhich is also listed (by Gluckman and Satterlee)Co.,

B.F.A.,are Joseph and Robert S. Bartless, Bing

B. FA Co.is in fact their maker’s mark,

To the stock and lock, Remington fitted a barrel

This same basic sidelock rifle can be found in a

The plainest form of this rifle has only a brass butt

characteristically rectanguin shape, a rifle fitted withlar with mitred corners,

Rigby flatson a round barrel, turned

This arm gives evidence of its Remington origins

This handsome rifle has seen better days but still

Rigby flats.It

perOn one at least, he put his salescussion target rifles.

Among little details of outline and shaping which

Remingtonto the collector’s eye is a

Americantype, all were in some part identifiedsporting rifle

Remington.The inescapable conclusion is that the

teatshape to the

Remington Arms was soon to fill a large role in the

The fact is that E. Remington & Sons from the time

Remington primer lockwas slightly different

The

Rigby flattedbarrels exist on larger sizes of

recalled is about .50-inch, not exceptionally large. It

If Remington made so many rifles, where are they?

Warren, Albany or the retail salesmen’s stamps like

Any gunmaker worth his salt could slave over spoke

L. Devendorf, Cedarorville,

Utica N. Y„ M. James.

Comments

Post a Comment