From the catalog of Wallis and Wallis, British gun

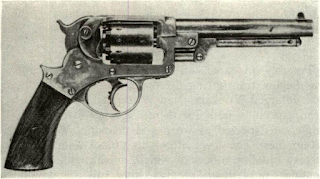

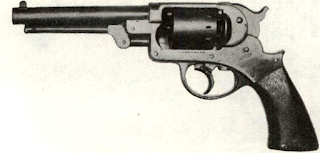

Lot 1060 ... A 6 shot .44 Starr SA Army Perc Rev 14",

Eben T. Starr of Yonkers, New York, might not have

To generations of gun collectors who pored over

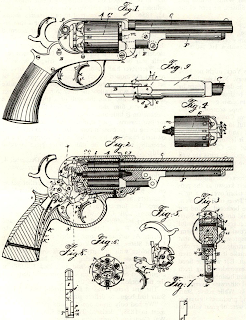

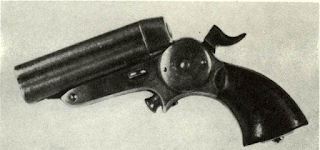

Starr’s second patent No. 30843, issued December 4,

, illustrated the perfected type of Starr double

Starr assigned his two patents plus a further patent

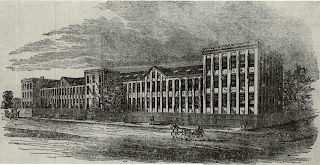

The first factory was at Binghamton, and by

NEW YORK, August 31,

Clapp set forth the schedule of delivery, 500 each

In September Starr proposed to increase the order

the first 1,000 were delivered of the new double

President Woolcott stepped into the fray and pre

it seems that had the sample been identical to those

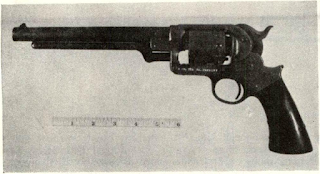

Starr also obtained a contract for 10,000 breech

The failure to mention Starr in the list worked against

The price of $20 for Navy .36 double action re

In explaining his decision to Secretary Stanton, Holt

The record reveals actual deliveries and payments

October 15, , 500 Navy revolvers purchased at $20.

November 19, , 500 Navy revolvers purchased at $20.

December 18, , 250 Navy revolvers purchased at

Army revolvers at $25 were accepted and paid for as

February 22, , 1,000 Army revolvers contract at $25.

March 25, , 600 Army revolvers contract at $25.

March 25, , 1,400 Army revolvers contract at $25.

Two stories with a heavy machinery ground floor

Automation is a fancy new word, but to the handi

From the first floor where the heavy drops or forges

Lot 1060 ... A 6 shot .44 Starr SA Army Perc Rev 14",

Col.Good Condition but action AsColt Address New York,

Eben T. Starr of Yonkers, New York, might not have

biteon it as a hitherto unknown Colt double action

modemrevolvers of the Civil War era.

To generations of gun collectors who pored over

Jones of Binghamton.Few have bothered to find outHe Pays The Freight.

Starr’s First Patents

Starr in obtained his first patent. Though thelifter leverof form similar to our accepted

lifter levertrigger. Secondly,

Starr’s second patent No. 30843, issued December 4,

, illustrated the perfected type of Starr double

Starr assigned his two patents plus a further patent

freeholder with property valued at over $40,000.

The first factory was at Binghamton, and by

We had only made one thousand for the Governdeclared Treasurer Clapp before thement in ,

andprior to August of .five hundred for the trade,

First Contracts

NEW YORK, August 31,

Clapp set forth the schedule of delivery, 500 each

In September Starr proposed to increase the order

the first 1,000 were delivered of the new double

President Woolcott stepped into the fray and pre

the armory in Binghamtonis employed exclusively in the manufacture of pistols.

the extent (ofIn detailing both failures to deliver rethis works) is exceeded only by the Colt establishment, in Hartford.

We were not ready to deliver in October (), but weThe fact that .36 caliber arms predominantly weresold to Major Hagner, in New York, 500, navy size, at $20, in that month. We also sold in like manner, 250, navy size, in November, and in the same month we sold 250, navy size, to the agent of Ohio. We have delivered and received certifi cates for 1,000, army size, in January; 600, army size in Feb ruary; 1,400, army size, in March, and we notified the depart ment that we had 1,000 ready for inspection March 28 or 29. The department immediately sent inspectors, who are now (April 10, ) at work.

army sizein Treasurer

it seems that had the sample been identical to those

Starr also obtained a contract for 10,000 breech

exigencies of our cavalry service,price $29. With

proposed tomake the whole Springfield gun, including the barrel.

We will make barrels from steel rodssaid Wolcott,

turns out theFor thework so that it requires more hand work than the Springfield musket machines ought to do.

Should the order for carbines be filled, we couldturn all our stock, machinery &c. to work upon the muskets without important loss. We are arms makers, have all our capital so engaged, and expect to continue in the business, having been at it now (April 15, ) for three years. We therefore must seek this kind of work, even if the Government do not employ us, Wolcott explained to the Commissioners.

Adverse Action by Commissioners

When Stanton called a screeching halt to the Warregular manufacturersand from whom Ripley wishedfor this department

The failure to mention Starr in the list worked against

regular manufacturers.

The price of $20 for Navy .36 double action re

In explaining his decision to Secretary Stanton, Holt

The record reveals actual deliveries and payments

October 15, , 500 Navy revolvers purchased at $20.

November 19, , 500 Navy revolvers purchased at $20.

December 18, , 250 Navy revolvers purchased at

Army revolvers at $25 were accepted and paid for as

February 22, , 1,000 Army revolvers contract at $25.

March 25, , 600 Army revolvers contract at $25.

March 25, , 1,400 Army revolvers contract at $25.

First Deliveries

First deliveries of the double-action revolvercostingat the renegotiated price oftwice as much as Colt’s

A New Factory

Possibly an expansion of revolver making facilitiesTwo stories with a heavy machinery ground floor

Automation is a fancy new word, but to the handi

Victorian

automation

From the first floor where the heavy drops or forges

Comments

Post a Comment