In sunny California a lady built a house. To San

Spread over six acres, within an estate of 160 acres, the

There is no adequate explanation of Mrs. Winchester’s actions. The legend grew that she was a

Cloudman also wrote of an action of the 1st D. C.

Popular in the border states, the Henry was bought

Beatty recalls in his diary on March 23, that,

All Henrys had the hand-loop lever extension of the

1,731 bought officially at a cost of $63,953.26 by the

Priced at $40, a Henry cost a lot of money to a

Pride of possession in his purchase was revealed by

I used to with a single shot rifle.” (Quoted from Oscar

C. Winther, With Sherman to the Sea).

In Letters from Lee’s Army the Southern point of

Putting this claim to the test, Kentuckian James M.

In consequence of this, Captain Wilson had fitted up a log

This caused a parley, resulting in their consent that he

them; the other two sprang for their horses. As the sixth

Wilson’s exhibition persuaded the Kentucky authorities that the gun was a good one for War; in token of

By one of those wry quirks of fate which so often

SIXTY SHOTS

This Rifle can be discharged 10 times without loading or taking

IT IS ALWAYS LOADED AND ALWAYS READY.

The size now made is 44-100 inch bore, 24 inch barrel, and car-

A resolute man, armed with one of these Stifles, particular-

"W. particularly commend it for A«*r U*M. .» the met e«ecliw arm for picket and ridett*

First class publicity, worthy of

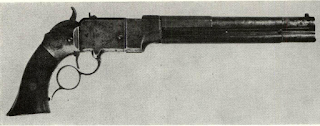

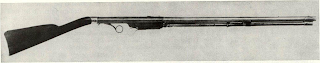

Sling for Henry was hooked to fixed loop on side of barrel-magazine assembly and to loop swivel based in side of stock.

happen when sales managers are more ingenious than

HQ. 1ST BRIGADE, 5TH DIV., 14TH ARMY CORPS

Murfreesboro, Tenn., March 20th,

Gentlemen:

At what price will you furnish me nine hundred of your

You will please afford the desired information at your

Yours respectfully,

J. T. WILDER

Though Winchester published Wilder’s letter, the

, Williamson (Harold F. Williamson, Winchester)

, production was stepped up about 25 per cent,

One regiment more realistically reporting on its full

The 1st D.C. Cavalry was attached to General

said he thought, by the way the bullets came into the

D.C. Cavalry trotted down the Jerusalem Turnpike.

The troopers moved out, their Henrys at the ready,

HEADQUARTERS 1ST D. C. CAVALRY

January 20th,

In connection with the accompanying report, I would beg

My regiment has been fully armed with these rifles, ever

General Kautz’s first raid in the month of May.

Battle at White’s Bridge, on the 8th of May.

Gen. Kautz’s second raid in Southern Virginia in the

The first attack on Petersburg on the 16th of June.

Gen. Wilson’s raid in Southern Virginia in the month of

The battle at Roanoke Bridge on the 27th of June.

The first battle at Ream’s Station on the 29th of June.

The first battle at Deep Bottom on the 25th, 26th, and

At the battle on the Weldon Railroad on the 21st, 22nd

The battle at Ream’s Station on the 25th of August.

The affair at Sycamore Church on the 16th of September.

Engagement on the Darbytown Road near Richmond on

From the experience I have had with this rifle, in the engagements above mentioned, and in numerous other affairs

The remarkable rapidity and accuracy with which the

present, and noticed the destructive effect of my fire upon

They carry with great accuracy; in target practice I have

For the cavalry service I prefer arms of calibre .44 in

Very respectfully, your ob’t servant,

J. S. BAKER,

Maj. Comd’g Reg’t

This lengthy endorsement, which may have cost

Flobert bulleted-breech cap .22

While B. Tyler Henry receives main credit for the

But the catalog does not describe these arms, and

For a man who was ignored, his designs swept the

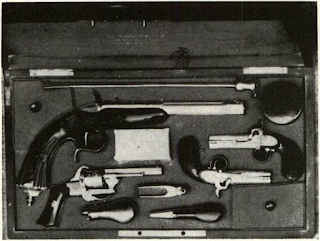

Cased gunmaker’s display set is in white, unfinished, ready

they were “early Smith & Wesson single shots.” It is

The “saloon” in which Flobert’s arms were used was

Flobert’s arms took the form of subcaliber or practice pistols for the deadly business of defending one’s

His arms, imported by Hartley, had a vogue ante-

Horace Smith is recorded as having manufactured

First Flobert concept was to use percussion cap much like

first patent of refers to a special kind of percussion cap and nipple, not necessarily a true breechloading arm at all. From the French patent specifica-

The cone evidently could accommodate a common

The next patent was granted to Flobert alone, still

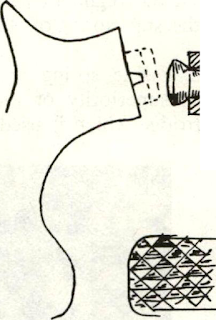

The drawing illustrates the hammer and breech-

Two innovations are introduced by the partners.

To the Flobert cartridge with its priming generally

So far as is known, the partners never made a gun

Hunt, Volcanic, Allen, Brown & Luther, are names

Hunt’s Rocket Ball

Hunt, it is believed, made only one model of his

The Jennings Repeater

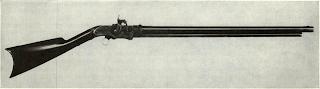

A shorter rifle than the Hunt model, the first-type

Jennings’ repeater proved too complicated, says

It remained for Horace Smith’s ultimate application

The principle of a prop-up block behind the true

A new rifle: This rifle, known as Jenning’s patent rifle,

The description is substantially accurate, though it

Contractor for the Jennings was Robbins and Lawrence, a machine works established at Windsor, Vermont about . The firm began with the association

Robbins & Lawrence accepted a further contract

Hunt, in developing his first rifle and cartridge, had

Robbins & Lawrence agreed in to build 5,000

The Great Exhibition opened on 1 May, .

Flobert attended the Great Exibition. The rifles and

Says Graham Burnside, in his very interesting and

“Maybe the gun came to us from Europe,” he con

“Loron was working with self-contained ammuni-

“When viewing a foreign product like the system

the Volcanic, but the contours of the pistol leave no

It was this design which occupied Smith upon his

A look at the patent reveals Williamson’s conjecture

There was no firing pin as we think of it today,

The gun and ammunition package Smith and Wesson

The other claims, which in one sense or another

It is an axiom of patent law, in the words of contemporary patent expert Ned Dickerson, that “you

Henry remained. His background of work at Springfield probably fitted him for planning out the ma-

By June of , Palmer and the mechanics were

Smith & Wesson

Which came first, is always a subject of interest

Taking a certain risk, we would like to set forth

First in production were the smallest pistols. In

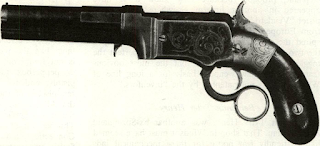

Smith was responsible for the small pistols. Evidencing pepperbox details, including the ring lever (found

Whether Smith proposed to use the Hunt rocket

Experiments continued even after setting the form

Courtlandt Palmer’s hopes for sales from such publicity were not to be fully realized; and in ten years Balti-

The Flobert cartridges of Smith were not suitable

The exact form of bullet used in the Smith & Wesson

Its cartridge was of lead and hollow, what has been termed

Crittenden & Tibbals made the balls for the Smith &

cap used on the No. 1 size had the same size hole as before,

It was a loaded ball of this complex construction,

Sales had been good, but disappointments and complaints even more than they expected. The mechanism

During August, , said Winchester, the machinery, tools, and fixtures, and arms, finished and

The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company of New

New Haven, February 8,

Daniel Baird Wesson

By vote of the Board of Directors of “The Volcanic Re-

Samuel L. Talcott, Secretary

Why this flight of talent and capital from the

Oliver F. Winchester

“O. F.” owned but $4,000 worth of the Volcanic

Winchester was a man of considerable intellectual

He took as partner John M. Davies, clothing jobber

, Winchester employed 800 people to cut shirts

Williamson makes an interesting statement about

The truth is, nobody in those days knew anything

, the J ournal-Courier, again quoting the Tribune,

I recall in meeting a Marine Corps sergeant

With Volcanic voted into bankruptcy, there was an

Exactly what the “inferior workmanship” was, is not

As much as he could, Hicks tried to correct things.

“We first made a single nipple or hook,” said Hicks,

“then single with two prongs, finally a double nipple

Meanwhile, Winchester had formed a new organization, the New Haven Arms Company. He proposed to

Volcanic stumbled along and failed to meet some

Volcanic carbines and ammunition in original boxes remained in storage at Volcanic Arms Co. when firm went into liquidation in February, . Guns were discovered in attic of Winchester in ’s or ’30’s, and placed by the main gate

Substantial factory was put up to turn out New Haven

were appointed trustees; Eli Whitney, Jr., Henry Newson, and Charles Ball, to make an inventory of the

Winchester arranged with the Tradesman’s Bank,

The guns made by all three firms, Smith & Wesson,

self never got to see this specimen or recognize it for

and rifles.

New Haven Arms Co., New Haven, -60

A price list of the New Haven Arms Company stated

“After buying the Smith & Wesson patents in ,”

B. Tyler Henry was responsible for the ultimate

With the growing tension throughout the nation,

Such a sweeping assignment seems not to have ever

The leverage of the odd finger lever must have

On the base of rimfire cartridges made by Winchester, a small “H” began to appear. This stood for Spread over six acres, within an estate of 160 acres, the

There is no adequate explanation of Mrs. Winchester’s actions. The legend grew that she was a

Origin of Winchester

Born in the furnaces of conflict, the New HavenCloudman also wrote of an action of the 1st D. C.

Popular in the border states, the Henry was bought

Beatty recalls in his diary on March 23, that,

The Henry Rifle

This prodigy of small arms, the Henry rifle, wasAll Henrys had the hand-loop lever extension of the

1,731 bought officially at a cost of $63,953.26 by the

Priced at $40, a Henry cost a lot of money to a

Pride of possession in his purchase was revealed by

I used to with a single shot rifle.” (Quoted from Oscar

C. Winther, With Sherman to the Sea).

In Letters from Lee’s Army the Southern point of

Exploits of the Henry

Putting this claim to the test, Kentuckian James M.

In consequence of this, Captain Wilson had fitted up a log

This caused a parley, resulting in their consent that he

them; the other two sprang for their horses. As the sixth

Wilson’s exhibition persuaded the Kentucky authorities that the gun was a good one for War; in token of

By one of those wry quirks of fate which so often

SIXTY SHOTS

HENRY'S PATENT

This Rifle can be discharged 10 times without loading or taking

IT IS ALWAYS LOADED AND ALWAYS READY.

The size now made is 44-100 inch bore, 24 inch barrel, and car-

A resolute man, armed with one of these Stifles, particular-

"W. particularly commend it for A«*r U*M. .» the met e«ecliw arm for picket and ridett*

First class publicity, worthy of

Sling for Henry was hooked to fixed loop on side of barrel-magazine assembly and to loop swivel based in side of stock.

|

| Side position of Henry sling fittings are more clearly seen in this left side elevation. Brass frame was easily machined, but production was slow and not until 1863 were deliveries fairly regular |

HQ. 1ST BRIGADE, 5TH DIV., 14TH ARMY CORPS

Murfreesboro, Tenn., March 20th,

Gentlemen:

At what price will you furnish me nine hundred of your

You will please afford the desired information at your

Yours respectfully,

J. T. WILDER

Though Winchester published Wilder’s letter, the

, Williamson (Harold F. Williamson, Winchester)

, production was stepped up about 25 per cent,

One regiment more realistically reporting on its full

The 1st D.C. Cavalry was attached to General

said he thought, by the way the bullets came into the

D.C. Cavalry trotted down the Jerusalem Turnpike.

The troopers moved out, their Henrys at the ready,

“A heavy force of mounted rebels had crossed theThe story of a few men prevailing against great oddsbridge, and with wild yells was charging up the hill, outnumbering our men two to one. On, on they came, expecting an easy victory. Coolly our men waited. Not a shot was fired till they were within easy range. Then a few volleys from the sixteen shooters sent them back in confusion. A second time they charged, with the same result. This time they did not return.”

HEADQUARTERS 1ST D. C. CAVALRY

January 20th,

In connection with the accompanying report, I would beg

My regiment has been fully armed with these rifles, ever

General Kautz’s first raid in the month of May.

Battle at White’s Bridge, on the 8th of May.

Gen. Kautz’s second raid in Southern Virginia in the

The first attack on Petersburg on the 16th of June.

Gen. Wilson’s raid in Southern Virginia in the month of

The battle at Roanoke Bridge on the 27th of June.

The first battle at Ream’s Station on the 29th of June.

The first battle at Deep Bottom on the 25th, 26th, and

At the battle on the Weldon Railroad on the 21st, 22nd

The battle at Ream’s Station on the 25th of August.

The affair at Sycamore Church on the 16th of September.

Engagement on the Darbytown Road near Richmond on

From the experience I have had with this rifle, in the engagements above mentioned, and in numerous other affairs

The remarkable rapidity and accuracy with which the

present, and noticed the destructive effect of my fire upon

They carry with great accuracy; in target practice I have

For the cavalry service I prefer arms of calibre .44 in

Very respectfully, your ob’t servant,

J. S. BAKER,

Maj. Comd’g Reg’t

This lengthy endorsement, which may have cost

“The 1stAnd in spite of an exposed magazine spring andDistrict of Columbia cavalry was in my command during the past year, and was exceedingly efficient; and had the discipline of the regiment been in proportion to the arm they carried, which is the ‘Henry rifle,’ the efficiency of the regiment would have been still greater. The valuable service which the regiment performed was, in the main, due to the superiority of the arm they carried.”

Flobert bulleted-breech cap .22

While B. Tyler Henry receives main credit for the

Louis Flobert

Louis Nicholas Auguste Flobert is a man little recorded in the annals of firearms inventors, though hisBut the catalog does not describe these arms, and

For a man who was ignored, his designs swept the

Cased gunmaker’s display set is in white, unfinished, ready

they were “early Smith & Wesson single shots.” It is

The “saloon” in which Flobert’s arms were used was

Flobert’s arms took the form of subcaliber or practice pistols for the deadly business of defending one’s

His arms, imported by Hartley, had a vogue ante-

Horace Smith is recorded as having manufactured

First Flobert concept was to use percussion cap much like

first patent of refers to a special kind of percussion cap and nipple, not necessarily a true breechloading arm at all. From the French patent specifica-

The cone evidently could accommodate a common

The next patent was granted to Flobert alone, still

The drawing illustrates the hammer and breech-

Smith and Wesson’s Cartridge

It was this cartridge which Horace Smith and DanielTwo innovations are introduced by the partners.

To the Flobert cartridge with its priming generally

So far as is known, the partners never made a gun

Hunt, Volcanic, Allen, Brown & Luther, are names

Hunt’s Rocket Ball

Hunt, it is believed, made only one model of his

The Jennings Repeater

A shorter rifle than the Hunt model, the first-type

Jennings’ repeater proved too complicated, says

It remained for Horace Smith’s ultimate application

The principle of a prop-up block behind the true

A new rifle: This rifle, known as Jenning’s patent rifle,

The description is substantially accurate, though it

Contractor for the Jennings was Robbins and Lawrence, a machine works established at Windsor, Vermont about . The firm began with the association

Robbins & Lawrence accepted a further contract

Hunt, in developing his first rifle and cartridge, had

Robbins & Lawrence agreed in to build 5,000

The Great Exhibition opened on 1 May, .

Flobert attended the Great Exibition. The rifles and

The Vendetti Pistol

There has come to the attention of American pistolSays Graham Burnside, in his very interesting and

“Maybe the gun came to us from Europe,” he con

“Loron was working with self-contained ammuni-

“When viewing a foreign product like the system

|

Early lever pistol made by Smith |

“We also have seen Vendetti pistols that appearThere is much sense in Burnside’s speculation,almost identical in function to the Volcanics, that have a chamber to accept a cartridge case. I do not know of such a cartridge (Burnside’s field of arms scholarship is cartridge history) . . . but it is obvious that it was a rimfire type utilizing a double striker. This ties in with Smith and Wesson’s intended cartridge, and even the double striker as used in the later Henry rifles. The odds are, that these Vendetti pistols are earlier than our American Volcanic.”

It was this design which occupied Smith upon his

A look at the patent reveals Williamson’s conjecture

There was no firing pin as we think of it today,

The gun and ammunition package Smith and Wesson

The other claims, which in one sense or another

It is an axiom of patent law, in the words of contemporary patent expert Ned Dickerson, that “you

Benjamin Tyler Henry

Benjamin Tyler Henry was another ex-SpringfieldHenry remained. His background of work at Springfield probably fitted him for planning out the ma-

By June of , Palmer and the mechanics were

Smith & Wesson

Which came first, is always a subject of interest

Taking a certain risk, we would like to set forth

First in production were the smallest pistols. In

Smith was responsible for the small pistols. Evidencing pepperbox details, including the ring lever (found

Whether Smith proposed to use the Hunt rocket

Experiments continued even after setting the form

Courtlandt Palmer’s hopes for sales from such publicity were not to be fully realized; and in ten years Balti-

The Flobert cartridges of Smith were not suitable

The exact form of bullet used in the Smith & Wesson

Its cartridge was of lead and hollow, what has been termed

Crittenden & Tibbals made the balls for the Smith &

cap used on the No. 1 size had the same size hole as before,

It was a loaded ball of this complex construction,

Sales had been good, but disappointments and complaints even more than they expected. The mechanism

Smith & Wesson Shop Sold

Sale of the Smith & Wesson shop at Norwich wasDuring August, , said Winchester, the machinery, tools, and fixtures, and arms, finished and

|

| Beginnings of mighty Winchester-Western armaments em- |

New Haven, February 8,

Daniel Baird Wesson

By vote of the Board of Directors of “The Volcanic Re-

Samuel L. Talcott, Secretary

Why this flight of talent and capital from the

Oliver F. Winchester

“O. F.” owned but $4,000 worth of the Volcanic

Winchester was a man of considerable intellectual

He took as partner John M. Davies, clothing jobber

|

| Volcanic .41 was reputed to have |

Williamson makes an interesting statement about

The truth is, nobody in those days knew anything

, the J ournal-Courier, again quoting the Tribune,

“The (Volcanic) pistol used on the occasion wasThe ballisticians of the modern-day Winchester firman 8-inch barrel, which discharged nine balls in rapid succession. The colonel fired shots which would do credit to a rifleman. He fired at an 8-inch diameter target at 100 yards, putting 9 balls inside the ring. He then moved back to a distance of 200 yards, and fired 9 balls more, hitting the target seven times. He then moved back 100 yards further, a distance of 300 yards from the mark, and placed five of the nine balls inside the ring, and hitting the bullseye twice. The man who beats that may brag.”

I recall in meeting a Marine Corps sergeant

With Volcanic voted into bankruptcy, there was an

Exactly what the “inferior workmanship” was, is not

As much as he could, Hicks tried to correct things.

“We first made a single nipple or hook,” said Hicks,

“then single with two prongs, finally a double nipple

Meanwhile, Winchester had formed a new organization, the New Haven Arms Company. He proposed to

Volcanic stumbled along and failed to meet some

Volcanic carbines and ammunition in original boxes remained in storage at Volcanic Arms Co. when firm went into liquidation in February, . Guns were discovered in attic of Winchester in ’s or ’30’s, and placed by the main gate

Substantial factory was put up to turn out New Haven

were appointed trustees; Eli Whitney, Jr., Henry Newson, and Charles Ball, to make an inventory of the

Winchester arranged with the Tradesman’s Bank,

The guns made by all three firms, Smith & Wesson,

self never got to see this specimen or recognize it for

Caliber | Weapon |

.30 | 4" pistol |

.38 | 8" pistol (“Navy”) |

jlcanic Repeating Arms Co., New Haven, -7 | |

.30 | 4"" pistol |

.30 | 6" pistol |

.38 | 6" pistol |

.38 | 8" pistol |

.38 | 8" pistol with stock |

.38 | 16%", 21", 25" carbines |

New Haven Arms Co., New Haven, -60

.30 | 4" pistol |

.30 | 6" pistol |

.40 | 6" pistol |

.40 | 8" pistol |

.40 | 16Vi", 21", 25" carbines |

and rifles. |

“After buying the Smith & Wesson patents in ,”

B. Tyler Henry was responsible for the ultimate

With the growing tension throughout the nation,

Such a sweeping assignment seems not to have ever

The leverage of the odd finger lever must have

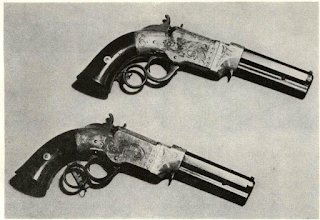

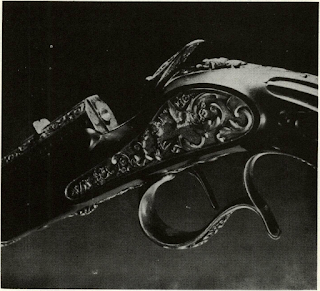

Handsome pair of .31 caliber

|

Comments

Post a Comment