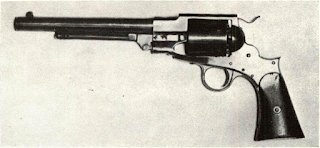

Hoard had obtained ratification of his Springfield

intending to effect an improvement by preparing a

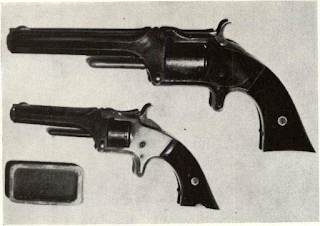

Manufacturer was C. B. Hoard, who produced a

shooters at his Watertown, New York, remodeled farm

intending to effect an improvement by preparing a

Manufacturer was C. B. Hoard, who produced a

shooters at his Watertown, New York, remodeled farm

Comments

Post a Comment