The patent genealogy of the Pettengill (often misspelled Pettingill) was threefold. The basic pepperbox

. Because of the close similarity between the

By December, , Rogers & Spencer had established a shop in Millvale, Oneida County, New York,

But Rogers & Spencer were to receive a decided shock

Rogers and Spencer had asked their partner, George

C. Tallman, of Washington, D. C. to deliver a pistol to

When the Commission came to consider whether the

SPRINGFIELD ARMORY,

May 20,

General Ripley,

SIR: In compliance with your instructions to me, dated

The firing was accurate, and the penetration good, the balls

Mr. Tallman was of opinion that the objections could be

It was again presented for trial a few days since, and has

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

A. B. DYER, Captain of Ordnance

As a consequence of this report, Hagner directed

He pointed out that the “serious objection” of double

had tried to comply. To compromise, Rogers offered

Most Pettengills seen have the thumb screw, so apparently this was not required; the change in the

Battlefield use of these arms is not well recorded;

When Rogers & Spencer confirmed their Pettengill

We have no disposition to urge upon our government an

At the time, Major Hagner could only urge the acceptance of the 2,000 order, but it was to appear in the

They were ready to go again and make “some army

Ordnance Office, War Department,

Respectfully & c

A. B. Dyer

Utica, New York

The arm which Rogers now prepared was made

especially Colts and Remingtons, were pouring into

The pistols remained in storage at New York

“We had the entire lot of 5,000 that was contracted

Ironically, the $60,000 worth of revolvers in

when Starr revolvers, used, went at $8 each. But General Dyer felt so attached to them that he refused to

For the right to make these revolvers, which they

. Because of the close similarity between the

By December, , Rogers & Spencer had established a shop in Millvale, Oneida County, New York,

. . . we are making the Pettingill (sic) pistol, a very superior arm for cavalry, belt or any other army service, ofThe lead time of three months pretty definitely establishes that Rogers & Spencer did not have the .44any size, of finish and material equal to the sample we present for your inspection . . . We are prepared to manufacture these pistols, army size, at the rate of 1,000 in ninety days, and 1,000 per month thereafter; and at this rate we should be glad to receive so large an order as the government please to give . . . We will make and deliver, of the army size, any number, for $20 each pistol, at times above indicated . . .

But Rogers & Spencer were to receive a decided shock

Rogers and Spencer had asked their partner, George

C. Tallman, of Washington, D. C. to deliver a pistol to

When the Commission came to consider whether the

SPRINGFIELD ARMORY,

May 20,

General Ripley,

SIR: In compliance with your instructions to me, dated

The firing was accurate, and the penetration good, the balls

Mr. Tallman was of opinion that the objections could be

It was again presented for trial a few days since, and has

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

A. B. DYER, Captain of Ordnance

As a consequence of this report, Hagner directed

He pointed out that the “serious objection” of double

|

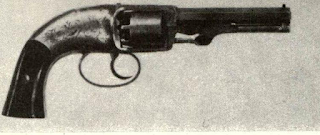

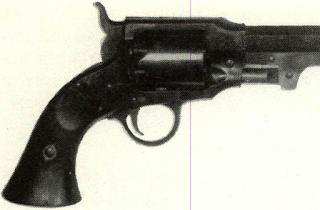

| Comparison of Army .44 sixshooter and small Pettengill in .31 caliber shows not only difference in size but difference in loading lever latching. Bottom pistol had two studs and lever arm was cramped between them when not in use. |

had tried to comply. To compromise, Rogers offered

Most Pettengills seen have the thumb screw, so apparently this was not required; the change in the

Battlefield use of these arms is not well recorded;

When Rogers & Spencer confirmed their Pettengill

We have no disposition to urge upon our government an

At the time, Major Hagner could only urge the acceptance of the 2,000 order, but it was to appear in the

They were ready to go again and make “some army

Ordnance Office, War Department,

Respectfully & c

A. B. Dyer

Utica, New York

The arm which Rogers now prepared was made

|

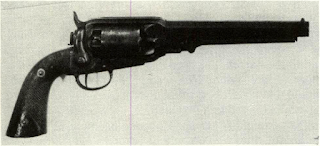

| Standard Rogers & Spencer revolver is apparently covered |

|

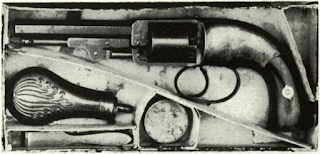

Sidehammer design of Ben Joslyn was rather bulky. Layout |

The pistols remained in storage at New York

“We had the entire lot of 5,000 that was contracted

Ironically, the $60,000 worth of revolvers in

when Starr revolvers, used, went at $8 each. But General Dyer felt so attached to them that he refused to

For the right to make these revolvers, which they

I have an unmarked Pettengill Heavy Army serial number 3426. There are no patent or maker or location stamps. Was the a prototype or a testing gun and not meant for actual sale?

ReplyDeleteHello, Boy that cardboard boxed/ cased Pocket Model Pettengill is rare. Has anyone seen it recently or know any more about it. It is very unusual to see. Thanks for any answer. Nick

ReplyDeleteI have a Pettengill "34" Navy but it mics out at .36 cal for sure !!

ReplyDelete