George Wright was principally to blame, except for

General Ripley wrote to Wright in unmistakable

The two went to “Liege or Cologne, where I commenced duty,” as Wright put it. “I found at Cologne

“Of the other lots of guns inspected at Vienna, I

I inspected there and I can form no estimate. I do not

One rifle noted as “the Marseilles arm” proved

One rifle noted as “the Marseilles arm” proved

These guns, I find, are all old and have evidently seen

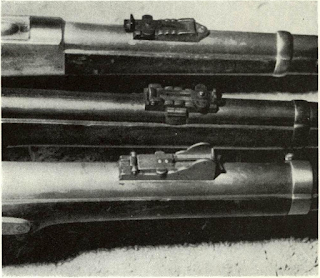

The ramrod is cupped for the round ball, as of course

The hausse is a simple standing sight and leaf folding on

As they are grooved, but so grooved as to be incapable of

So much at variance with the terms of Boker’s

From these records of purchases they had negotiated emerged a tabulation of 20 individual lots of arms,

The Civil War historian must remember that these

Herman Boker & Co. Firearms (Muskets Rifles) -62

Total, 188,054 rifles and rifle muskets to a value of

This and the other accounts of Boker for sabers was

General Ripley wrote to Wright in unmistakable

The two went to “Liege or Cologne, where I commenced duty,” as Wright put it. “I found at Cologne

“My course of inspection,” Wright continued, “wasThe number of boxes Wright would open dependedto take up a gun from the box, requiring a box here and there to be opened for me, to feel the strength of the mainspring, the fit and spring of the ramrod, the fit and the material of the bayonet. I did not take a lock off, except once. I suppose I have taken off a dozen barrels and taken out the breech pins, to see about the rifling. I went away in such haste I had nothing to inspect a gun with except a taper gauge for caliber.”

“Of the other lots of guns inspected at Vienna, I

I inspected there and I can form no estimate. I do not

One rifle noted as “the Marseilles arm” proved

One rifle noted as “the Marseilles arm” proved These guns, I find, are all old and have evidently seen

The ramrod is cupped for the round ball, as of course

The hausse is a simple standing sight and leaf folding on

As they are grooved, but so grooved as to be incapable of

So much at variance with the terms of Boker’s

From these records of purchases they had negotiated emerged a tabulation of 20 individual lots of arms,

The Civil War historian must remember that these

Herman Boker & Co. Firearms (Muskets Rifles) -62

Class 1 | 4,440 at | $5.13 | $22,777.20 |

Class 2 | 600 at | 5.47% | 3,283.20 |

Class 3 | 1,992 at | 5.70 | 11,354.40 |

Class 4 | 7,931 at | 6.27 | 49,727.37 |

Class 5 | 12,332 at | 6.84 | 84,350.88 |

Class 6 | 5,488 at | 7.98 | 43,794.24 |

Class 7 | 4,588 at | 8.66% | 39,750.43 |

Class 8 | 847 at | 10.26 | 8,690.22 |

Class 9 | 3,928 at | 10.484/s | 41,196.86 |

Class 10 | 6,940 at | 10.71% | 74,369.04 |

Class 11 | 4,100 at | 11.40 | 46,740.00 |

Class 12 | 9,350 at | 11.51% | 107,655.90 |

Class 13 | 236 at | 12.54 | 2,959.44 |

Class 14 | 3,486 at | 12.82Vi | 44,707.95 |

Class 15 | 21,945 at | 13.11 | 287,698.95 |

Class 16 | 1,824 at | 13.68 | 24,952.32 |

Class 17 | 25,247 at | 14.52Vi | 366,965.14 |

Class 18 | 2,272 at | 14.82 | 33,671.04 |

Class 19 | 51,819 at | 15.671/2 | 812,262.82 |

Class 20 | 18,689 at | 16.40 | 306,499.60 |

This and the other accounts of Boker for sabers was

Comments

Post a Comment