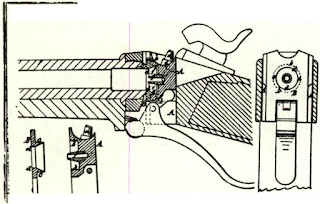

The basic principle of toggle-linking trigger guardlever and vertically sliding breechblock dated from that

patent. Sharps’ sliding wedge breechblock is still with

No finer piece of precision manufacturing in steel

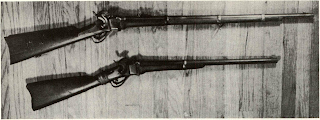

The “Model ” was the basis for the Civil War

Winston O. Smith’s The Sharps Rifle (Morrow &

R. S. LAWREJfCE

Dec. 20,.

To make possible the cleaning of the central section of the

The Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company used special

It is interesting to note that the tumblers, bridles, mainsprings, and mainspring swivels of these later models (

In , almost a century after it was made, I

|

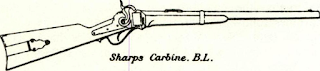

Sharps New Model carbine illustrated in Official |

No finer piece of precision manufacturing in steel

The “Model ” was the basis for the Civil War

Winston O. Smith’s The Sharps Rifle (Morrow &

R. S. LAWREJfCE

Dec. 20,.

To make possible the cleaning of the central section of the

The Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company used special

It is interesting to note that the tumblers, bridles, mainsprings, and mainspring swivels of these later models (

In , almost a century after it was made, I

Comments

Post a Comment