The Yankees were not the only ones with long-range rifles. During the siege of Charleston, South Carolina, the Union forces were under continual small arms fire from long range. Their artillery batteries were pounding the city, but one by one a blue-clad sponger and rammer would drop suddenly, a bullet through his head as he stood beside the smoking muzzle of his cannon. The 144th Regiment New York Volunteer Infantry served in this fighting. Some men stationed in Fort Wagner, a Union artillery strong point from which Charleston was being shelled, complained “Nor was the danger alone from (Confederate) shells, for on a Rebel picket line among the sand hills in front of Fort Wagner the sharp shooters had established themselves. These sharp shooters were provided with the Whitworth rifle with telescopic attachment and from their little sand-bag batteries, established in the sand hills, they watched

By Act of Congress in Richmond in , a formal Confederate sharpshooter regiment was organized on

This “wonder rifle,” accurate at seven times the range

At short ranges the Enfield and Whitworth rifles

Whitworth rifles weren’t British general issue, but a

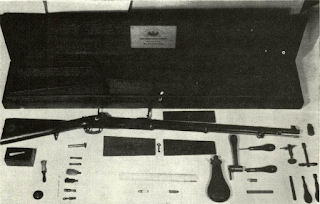

Fittings on his rifles were like those of the standard

The scope sights fitted were less cumbersome than

By Act of Congress in Richmond in , a formal Confederate sharpshooter regiment was organized on

This “wonder rifle,” accurate at seven times the range

At short ranges the Enfield and Whitworth rifles

Whitworth rifles weren’t British general issue, but a

Fittings on his rifles were like those of the standard

The scope sights fitted were less cumbersome than

Comments

Post a Comment