Three Sharps long guns were made in Hartford for

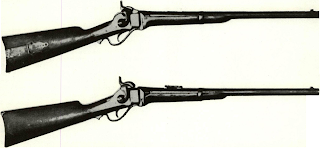

All Civil War Sharps arms were percussion cap, using a combustible cartridge of glazed linen. In the front

In the author’s collection is a Sharps 30-inch New

the merits of the Sharps guns. Though Colt in his controversial way had once urged his agent in the west

General Ben Butler upon taking command in Baltimore immediately purchased 200 New Model

For a lawyer, Ben Butler drew up a cloudy contract.

stock mortise surrounding the block spring, underneath the barrel. This can build up and if a trace of

The excitement of Bull Run caused many changes

Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company

Hartford, July 9,

It is our understanding that each arm is accompanied by

Respectfully &c

J. C. Palmer, President.

General J. W. Ripley

By March 8, , starting with 300 carbines delivered September 13, , Palmer had turned in 8,800 accepted carbines. Deliveries were so much according to schedule and quality so high, that Ripley named

Palmer did not have to come to Washington to defend himself against Holt and Owen in their relentless

We are not certain if he took all of Bean’s 500 Sharps

Palmer sold directly to the United States 100 sword

Bean ultimately delivered 100 carbines at $30 on

of General Nathaniel Banks’ “U. S. Police” force

The 6,000 carbines Palmer was making were inspected in an unusual fashion, for contract arms. They

This should refer to a new Model carbine without detailed inspectors’ marks under the finishing on

February 15, : send “soon as made” 343 Sharps carbines

June 26, : “all the Sharps carbines you can manufacture

September 9, : “all the Sharps carbines you can manufacture for the three months next ensuing after the expiration

December 19, : “all you can deliver for three months”

All Civil War Sharps arms were percussion cap, using a combustible cartridge of glazed linen. In the front

In the author’s collection is a Sharps 30-inch New

the merits of the Sharps guns. Though Colt in his controversial way had once urged his agent in the west

General Ben Butler upon taking command in Baltimore immediately purchased 200 New Model

For a lawyer, Ben Butler drew up a cloudy contract.

stock mortise surrounding the block spring, underneath the barrel. This can build up and if a trace of

The excitement of Bull Run caused many changes

Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company

Hartford, July 9,

It is our understanding that each arm is accompanied by

Respectfully &c

J. C. Palmer, President.

General J. W. Ripley

By March 8, , starting with 300 carbines delivered September 13, , Palmer had turned in 8,800 accepted carbines. Deliveries were so much according to schedule and quality so high, that Ripley named

Palmer did not have to come to Washington to defend himself against Holt and Owen in their relentless

We are not certain if he took all of Bean’s 500 Sharps

Palmer sold directly to the United States 100 sword

Bean ultimately delivered 100 carbines at $30 on

of General Nathaniel Banks’ “U. S. Police” force

The 6,000 carbines Palmer was making were inspected in an unusual fashion, for contract arms. They

This should refer to a new Model carbine without detailed inspectors’ marks under the finishing on

February 15, : send “soon as made” 343 Sharps carbines

June 26, : “all the Sharps carbines you can manufacture

September 9, : “all the Sharps carbines you can manufacture for the three months next ensuing after the expiration

December 19, : “all you can deliver for three months”

Comments

Post a Comment