While the 10-shooters and double pistols were in

The site of the Walch-Lindsay factory is open to

Double musket used two regulation .58 charges. Right hammer fired

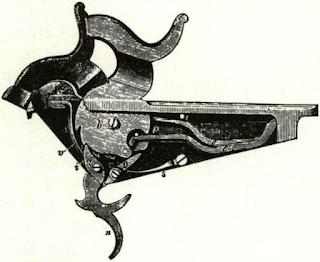

Cut No. 1 represents interior of Lock, b b Hammers, e e Main Spring, i i Scears, v v Scear Springs, r

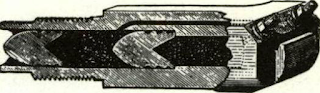

Cut No. 2 represents the inner scction of breech, with two charges in position.

General Formation. The double lock is inserted into the stock directly in rear of barrel. The barrel

Construction. The bottom of the bore is decreased in size, forming a chamber. (See cut No. 2.) This

Ammunition used should always be the regular Springfield paper pressed ball cartridge. Full size for caliber Grooves in ball should be fiUed with lubrication. Fire cannot pass back to rear charge, if the

musket. Of this gun he says: “United States Muzzle

How far back into history the Springfield Armory

It is such tales as this that make one of the regrets

On December 17, , John P. Lindsay of New

had been ordered as a consequence of a trial held by

Benet’s letter to Ripley reporting the results describes the musket and its purpose in detail; and was

The object of the invention is to be enabled to load the

Regrettably, Lindsay did not reproduce the target

Who made them, remains something of a mystery,

The name of a man guaranteeing the contract’s fulfillment was usually the name of a man who had an

The site of the Walch-Lindsay factory is open to

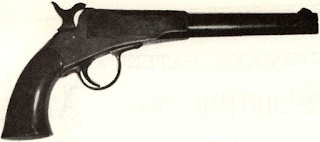

Double musket used two regulation .58 charges. Right hammer fired

|

| LINDSAY’S PATENT |

|

| No. 2. |

|

| No. 3. |

Cut No. 1 represents interior of Lock, b b Hammers, e e Main Spring, i i Scears, v v Scear Springs, r

Cut No. 2 represents the inner scction of breech, with two charges in position.

General Formation. The double lock is inserted into the stock directly in rear of barrel. The barrel

Construction. The bottom of the bore is decreased in size, forming a chamber. (See cut No. 2.) This

Ammunition used should always be the regular Springfield paper pressed ball cartridge. Full size for caliber Grooves in ball should be fiUed with lubrication. Fire cannot pass back to rear charge, if the

musket. Of this gun he says: “United States Muzzle

How far back into history the Springfield Armory

It is such tales as this that make one of the regrets

On December 17, , John P. Lindsay of New

|

| No. 1. |

|

Principle of two-shooter was applied by Lindsay to big |

Benet’s letter to Ripley reporting the results describes the musket and its purpose in detail; and was

The object of the invention is to be enabled to load the

Regrettably, Lindsay did not reproduce the target

Who made them, remains something of a mystery,

The name of a man guaranteeing the contract’s fulfillment was usually the name of a man who had an

Comments

Post a Comment