Christian Sharps’ personal career had separated from

Using a rimfire metallic cartridge, they were breechloading single shots, in which the frame extended far

Wesson small revolvers, made such an arm but in percussion, not cartridge, form. Otherwise it looks much

Sometime in the summer of , as Holt and

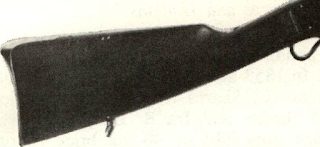

Four basic Sharps & Hankins long guns have been

The S & H Rifle had a 32Vi-inch round barrel,

The “improved” Sharps & Hankins is improperly

These make three basic Sharps & Hankins guns,

Using a rimfire metallic cartridge, they were breechloading single shots, in which the frame extended far

|

| The Walch-Lindsay pistols described on page 283. The .36 |

Wesson small revolvers, made such an arm but in percussion, not cartridge, form. Otherwise it looks much

Sometime in the summer of , as Holt and

Ordnance Office, War Department

Gentlemen: Your letter of the 12th instant is received.

into the bore in these of 55 or 60 grains) prepared for a ball

Respectfully &c.,

George D. Ramsay,

Brigadier General, Chief of Ordnance

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The projectile shown is a long .44 bullet having an Four basic Sharps & Hankins long guns have been

The S & H Rifle had a 32Vi-inch round barrel,

The “improved” Sharps & Hankins is improperly

These make three basic Sharps & Hankins guns,

Comments

Post a Comment