Among the many stories of the sharpshooters’ exploits, none stands out more than the vaunted accomplishment of Captain John H. Metcalf, who is said to

and did not earn his honors as a rifleman, seems not to

“It was during the Red River Campaign in Louisiana

“Metcalf blinked again. The tent fly had suddenly

“Metcalf felt a great emptiness at the pit of his

“He touched his finger gently to the cold, curved

“A lieutenant pressed the button on his stopwatch

“Metcalf watched fascinated as the general spun

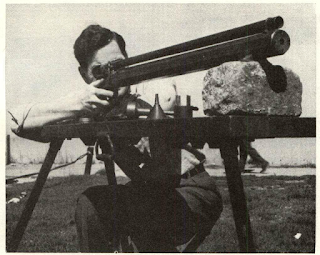

On page 89 Sawyer describes “No. 3, Heavy Target

Sawyer saw in this handsome rifle, an arm which

In carrying the narrative of “Metcalf” forward in

. . My staff did their duty well, and I cannot in justice

McMillan does not single Metcalf out for any special

It was in fact artillery under Captain Lynch and not

These big scope rifles were called “the heavies”

used in the rifle musket” is shown. This appears identical with the .58 regulation bullet, and since many of

The bullet used is important. A long, heavy bullet

and did not earn his honors as a rifleman, seems not to

“It was during the Red River Campaign in Louisiana

“Metcalf blinked again. The tent fly had suddenly

“Metcalf felt a great emptiness at the pit of his

“He touched his finger gently to the cold, curved

“A lieutenant pressed the button on his stopwatch

“Metcalf watched fascinated as the general spun

“Capt. John Metcalf allowed the great wearinessWhile Debevic does a creditable job of evoking thehe’d been fighting off so long to settle over him as he watched the Northern army break from cover and swarm across the valley. The victory was quick and overwhelming. The commendation which was issued shortly afterwards read: ‘To Captain John T. Metcalf for coolness and courage in the Red River Campaign, Louisiana, April, .’”

On page 89 Sawyer describes “No. 3, Heavy Target

Sawyer saw in this handsome rifle, an arm which

In carrying the narrative of “Metcalf” forward in

. . My staff did their duty well, and I cannot in justice

McMillan does not single Metcalf out for any special

It was in fact artillery under Captain Lynch and not

|

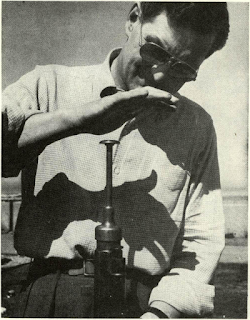

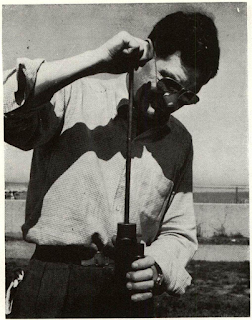

| Bullet seater fits over end of false muzzle and movable |

These big scope rifles were called “the heavies”

used in the rifle musket” is shown. This appears identical with the .58 regulation bullet, and since many of

The bullet used is important. A long, heavy bullet

Comments

Post a Comment