During the late winter and spring of the New

President Sharp’s Rifle Company, Hartford, Connecticut

The “parts deemed unessential and to be omitted hereafter” were mentioned in Ripley’s accompanying

Between May 15 and June 23 six shipments of

was signed for carbines, less ballet moulds, at $24;

Deliveries were regular in thousands, but on December 21. immediately following a delivery on 20 December of 1,000 carbines at the contract price of $24, 1,000 more guns were received at a special price of

Should any portion of the carbines herein contracted for be

The 1,000 second-class arms delivered must have

Rifles from Sharps were numbered in with the

Considering these were socket bayonet rifles, taking triangular bayonets (see Chapter 19), and that they

Chapter 12) that he delivered only to the United

From the other side, by adding the number of

Existing Sharps triangular bayonet rifles which have

Ordnance Office, April 1, Sir: By authority of the Secretary of War, this departmentJ. C. Palmer, Esq.will receive from you, at the current price of $30 for each carbine and appendages, all such carbines of the present pattern (i.e., New Model ) as you may now have completed, or in process of construction, with the parts deemed unessential, and to be omitted in those hereafter to be fabricated and bought at the reduced rate. All to be subject to inspection as heretofore. Major Hagner, inspector of contract arms, has been furnished with a copy of this order . . .

Iames W. RipleyBrigadier General, Chief of Ordnance

President Sharp’s Rifle Company, Hartford, Connecticut

The “parts deemed unessential and to be omitted hereafter” were mentioned in Ripley’s accompanying

Between May 15 and June 23 six shipments of

|

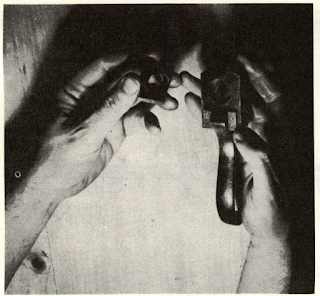

| Lawrence ring plate could be removed for cleaning. For modern shooting, back can be shimmed up and front surface ground smooth to improve gas-sealing qualities by cleaning off eroded area. |

was signed for carbines, less ballet moulds, at $24;

Deliveries were regular in thousands, but on December 21. immediately following a delivery on 20 December of 1,000 carbines at the contract price of $24, 1,000 more guns were received at a special price of

Should any portion of the carbines herein contracted for be

The 1,000 second-class arms delivered must have

Rifles from Sharps were numbered in with the

(Telegram)

Ordnance Office, January 27,An additional order for 1,000 more rifles, identicalJ. C. Palmer & Co. Hartford, Connecticut:

Send 1,000 Sharp’s rifles, with accoutrements, and 100,000cartridges, to Washington arsenal for Berdan’s sharpshooters. More by mail. Send as soon as possible.

Jas. W. Ripley, Brigadier General

Considering these were socket bayonet rifles, taking triangular bayonets (see Chapter 19), and that they

Chapter 12) that he delivered only to the United

From the other side, by adding the number of

Existing Sharps triangular bayonet rifles which have

Comments

Post a Comment