Back in , the legislature of New Jersey, when

After Sumter he proposed to Governor Buckingham to equip a regiment. “His other proposition is

Colt’s offer was accepted by Governor Buckingham

The regiment was almost at once fully manned.

As light infantry they were “active, strong men carefully selected from the rest of the regiment. Selected

1. The movements of skirmishers shall be subjected to such

2. * * *

3. When skirmishers are thrown out to clear the way for,

* * *

8. The movements of skirmishers will be executed in quick,

9. Skirmishers will be permitted to carry their pieces in

These were the shock troops, the men on point;

Perhaps the Governor became miffed because of the

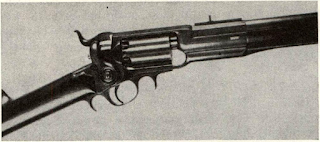

volving rifles. Three hundred Colt revolving rifles had

20, , declared: “The 1st Regiment Colt’s Revolving Rifles of Connecticut is hereby disbanded and all

Colt offered to start making 100 guns a week, one

After Sumter he proposed to Governor Buckingham to equip a regiment. “His other proposition is

Colt’s offer was accepted by Governor Buckingham

|

| View of Colt’s famous arms factory, which achieved the status of a “national works.” |

GHQ State of ConnecticutAdjutant Gen’l Ofc. Hfd May 16,Special Orders No. 83Sam Colt, Esquire, of Hartford is appointed Colonel 1stRegiment Colts Revolving Rifles of Connecticut. By order of the Commander in ChiefJ. D. Williams, Adjutant General

The regiment was almost at once fully manned.

As light infantry they were “active, strong men carefully selected from the rest of the regiment. Selected

1. The movements of skirmishers shall be subjected to such

2. * * *

3. When skirmishers are thrown out to clear the way for,

* * *

8. The movements of skirmishers will be executed in quick,

9. Skirmishers will be permitted to carry their pieces in

These were the shock troops, the men on point;

Perhaps the Governor became miffed because of the

volving rifles. Three hundred Colt revolving rifles had

20, , declared: “The 1st Regiment Colt’s Revolving Rifles of Connecticut is hereby disbanded and all

Colt offered to start making 100 guns a week, one

Comments

Post a Comment