The factory that the Rigdon Guards fought to save

Because Colonel E. C. Grier, Griswold’s son-in-law,

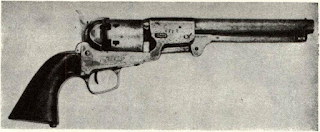

Years ago it was assumed by collectors that the

Because Colonel E. C. Grier, Griswold’s son-in-law,

Years ago it was assumed by collectors that the

Comments

Post a Comment