Hailing from Baltimore, and originally from England

Pearson’s sudden death at 10 a.m. August 1 was a

Circumstantial proof of this may appear in Mitchell’s

Several facts are in this brief statement: Colt wrote a

to his private account and not to the Company, because

When he was paid this sum by Colt is not known

An immigrant clockmaker from England, John

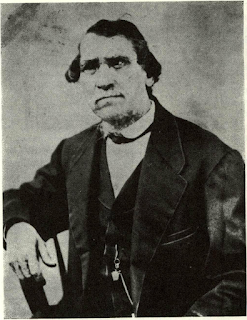

Mr. Pearson was a gunsmith and we may well say master ofhis trade. He should have been, as we verily believe, the recipient of honors attributed to Colt for the Colt’s patent firearms. He was one of the most ingenious of men, and a scientific workman, a sober, steady, industrious and honest man. He goes to his grave at the ripe age of 80, respected by all who knew him.

Pearson’s sudden death at 10 a.m. August 1 was a

Circumstantial proof of this may appear in Mitchell’s

Several facts are in this brief statement: Colt wrote a

|

Gunsmith John Pearson lost fortune he obtained from

|

When he was paid this sum by Colt is not known

An immigrant clockmaker from England, John

Comments

Post a Comment