In January, , Rigdon, Ansley & Company was

Ansley, though described by Rigdon as essential to

Another threat to the pistol factory by Yankee

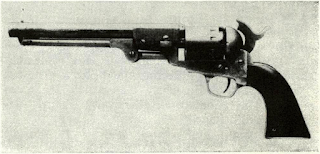

Rigdon’s Colt-type revolvers differ obviously from

While the form of the handles is well shaped and

With Jesse Ansley, Rigdon introduced a prominent

The Rigdon, Ansley & Company 12-stoppers (a

Rigdon may have struggled to keep the plant going

Ansley, though described by Rigdon as essential to

Another threat to the pistol factory by Yankee

Rigdon’s Colt-type revolvers differ obviously from

While the form of the handles is well shaped and

With Jesse Ansley, Rigdon introduced a prominent

The Rigdon, Ansley & Company 12-stoppers (a

Rigdon may have struggled to keep the plant going

Comments

Post a Comment