While the G & G was purchased at about $50 each

I propose to establish the manufactury in or near to the

... I would not be justified in embarking in the business

Burton asked for an advance of funds scheduled at

On November 30, , the C.S. War Department

The plant was shifted to Atlanta in the summer and

These drawings may not have been of much use to

A new contract, taking into account the rise in costs

during the month of February, for this curious March

5, , contract specifies delivery of 600 guns in

The principal purpose of this contract seem to have

Burton’s insistence now that the contractor himself

Up to this time about 700 revolvers had been

The move of the Spiller & Burr equipment to Macon

Cost of manufacture at Macon of the Spiller & Burr

rons had saved their Confederate money invested in

Haiman Brothers, Louis and Elijah, fared less well

It is a little misleading to say, as Albaugh has

Haiman, as an old workman, David Wolfson of

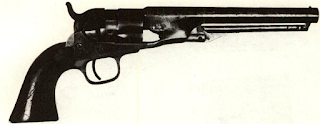

The “two men” may be Burton and Spiller, of Richmond. That “every part was made by machinery” is

I propose to establish the manufactury in or near to the

... I would not be justified in embarking in the business

Burton asked for an advance of funds scheduled at

On November 30, , the C.S. War Department

The plant was shifted to Atlanta in the summer and

These drawings may not have been of much use to

A new contract, taking into account the rise in costs

during the month of February, for this curious March

5, , contract specifies delivery of 600 guns in

The principal purpose of this contract seem to have

Burton’s insistence now that the contractor himself

Up to this time about 700 revolvers had been

The move of the Spiller & Burr equipment to Macon

Cost of manufacture at Macon of the Spiller & Burr

rons had saved their Confederate money invested in

Haiman Brothers, Louis and Elijah, fared less well

It is a little misleading to say, as Albaugh has

Haiman, as an old workman, David Wolfson of

The “two men” may be Burton and Spiller, of Richmond. That “every part was made by machinery” is

Comments

Post a Comment