About 7 a.m. February 5, , a fire was discovered

With the ice-choked Connecticut River a stone’s

The H-construction of the factory with the New

As previously described, in Colt’s factory

Close examination has not narrowed down the serial

Post-fire, the barrel stamp appears a little “larger”

Was it a bad gun? To the engineer interested in

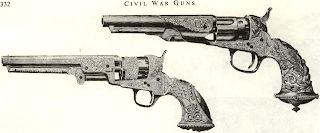

For the first time reproduced in any firearms history

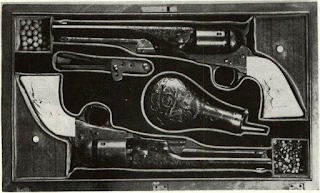

They form the “missing link,” we believe, to what

They were readying the works to fabricate a new

This frame conception is an advance upon the earlier

What the causes may have been for the failure of

The lack of endorsement on this letter prevents any

The Wartime output of Colt’s in the New Model

That this pistol, called by collectors “Model ,”

It was to the original creeping lever “New Model

That Colt was politically sensitive, as just stated,

A puzzle to collectors has been the presence of the

I will add for your guidance that the first 16 cases

Of this lot, some were parts of arms and were reshipped back to New York later, while 16 cases remained to become part of the invoice to J. P. Moore.

“The 1,700 with moulds & wrenches in cases

A solution to the problem of the different Hartford

He made a survey of the principal workmen in his

“You may rely upon it that not only will numbers

Hartley’s fear was a very real one of commercial

In urging the colonel to take care lest he lose

The safest thing was to restore the stamping of

COLT, NEW YORK, US AMERICA.

Arms seen with the Hartford mark include the New

Those guns sent to Moore, one of the Colt Allies,

Ames, by Moore, were to be shipped on South, said

In the Pocket Pistols, Schumaker suggests not more

These are not more precisely described, so it is

Some London-stamped guns made such a lengthy

It is said, “The credit for the revolver goes to

With the ice-choked Connecticut River a stone’s

The H-construction of the factory with the New

As previously described, in Colt’s factory

Close examination has not narrowed down the serial

Post-fire, the barrel stamp appears a little “larger”

Was it a bad gun? To the engineer interested in

For the first time reproduced in any firearms history

They form the “missing link,” we believe, to what

They were readying the works to fabricate a new

This frame conception is an advance upon the earlier

What the causes may have been for the failure of

The lack of endorsement on this letter prevents any

The Wartime output of Colt’s in the New Model

- The New Navy .36, a streamlined creeping lever

pistol en suite with the Army .44, but of course Navy size handle. A very few of these, probably under 100, had been made up with a special pattern of full fluted cylinder, when the change occurred to the smooth Navy-scene stamped cylinder in the Army series, so the Navy was changed to the Old Model cylinder to keep it uniform. Military deliveries included 1,000 New Model Navy at $22.50 February 17, , and 1,000 more April 2. An added 56 were bought January 26, , at $15, while commercial arms already in the trade were taken at varying retail prices when needed by the purchasing officers. About 40,000 New Model Navys were made. - New Model Police Pistol and New Model Pocket

Pistol of Navy Caliber. Though appearing in two forms, this is, we believe, a basic model which was supplied during the War indiscriminately. The basic

That this pistol, called by collectors “Model ,”

It was to the original creeping lever “New Model

That Colt was politically sensitive, as just stated,

A puzzle to collectors has been the presence of the

I will add for your guidance that the first 16 cases

Of this lot, some were parts of arms and were reshipped back to New York later, while 16 cases remained to become part of the invoice to J. P. Moore.

“The 1,700 with moulds & wrenches in cases

A solution to the problem of the different Hartford

He made a survey of the principal workmen in his

“You may rely upon it that not only will numbers

Hartley’s fear was a very real one of commercial

In urging the colonel to take care lest he lose

The safest thing was to restore the stamping of

COLT, NEW YORK, US AMERICA.

Arms seen with the Hartford mark include the New

Those guns sent to Moore, one of the Colt Allies,

Ames, by Moore, were to be shipped on South, said

In the Pocket Pistols, Schumaker suggests not more

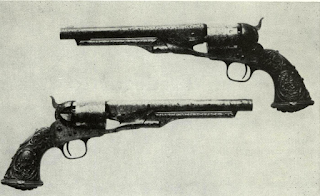

|

Stone’s River. Bottom set, in |

These are not more precisely described, so it is

Some London-stamped guns made such a lengthy

It is said, “The credit for the revolver goes to

Comments

Post a Comment