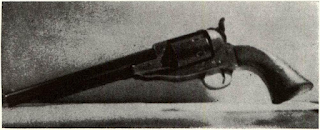

- Beware of any “unknown” Confederate revolver,

for though aspirations and contracts or offers of arms to be delivered in the future were many, the actual number of going gunmakers who fulfilled their responsibilities were few. - The modem home handyman with more junk

pistol parts and an equal helping of junk ethics is turning out Confederate pistols in quantity quite equal to the wistful cupidity of the collectors. There is more money around for Confederate sidearms than there are C.S.-made revolvers to buy. A typical Confederate revolver that in was referred to in awe as worth $300-$500, today cannot be bought for $1,500. One gun not even considered by many authorities to be “Confederate” (though it will be seen that we differ in this point of view) is the St. Louis-made Shawk & McLanahan. In we were queried as to the value of one; refused to say more than it is worth “several hundreds of dollars.” When we checked into the status of the gun a year later, we were informed that “It is still for sale and the price is $6,000.” Though of a limited production run, certain things did set it apart from the others of the same make. For a unique Confederate arm of importance, there is almost no limit to the prices asked. The destitute South has arisen again, not with money having 12-pounder Napoleons printed on the backs, but with good old United States Notes and Silver Certificates. Major market for the Confederate revolver is in the South, particularly among the better heeled Texans. To the buyer, caveat emptor is the maxim. - Unfortunately for the historian, the South had a

demand for revolvers almost as pressing as the financial demand today to fake something up. Second-hand parts, components sold off as non-standard by a big factory, limited production runs of Northern arms unmarked or with Southern issue-markings, all serve to confuse the serious researcher. Mingled with fakes of 40 or 50 years ago, now thoroughly aged, or refinished arms of two generations past now russetted into a semblance of “originality,” are the genuine individual pieces made as prototypes, shop or promotion models, or as a gun to defend Ol’ Massa when he went off to the War.

The skills of the Southern manor blacksmiths should

Comments

Post a Comment