Burton was a talented general engineer, it is true,

Whitney pistol ultimately built by Spiller & Burr. Regardless of the personal interest which this remarkable

Burton seems to have associated himself with potential manufacturers in an arms contract. He would then

Under government supervision, Downer estimated

Guns made by Robinson are found marked “S C.

which may be read “88—it is believed the stamps are

Though the Robinson shop represented a high degree of efficient mechanization, producing 500 carbines

Whitney pistol ultimately built by Spiller & Burr. Regardless of the personal interest which this remarkable

Burton seems to have associated himself with potential manufacturers in an arms contract. He would then

Under government supervision, Downer estimated

Guns made by Robinson are found marked “S C.

|

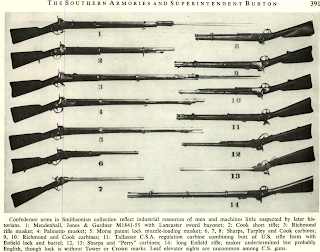

J. P. Murray rifle, like Mendenhall, Jones & Gardner, is combination of M and M U.S. styles.

|

Though the Robinson shop represented a high degree of efficient mechanization, producing 500 carbines

Comments

Post a Comment