In the event of attack on this arsenal, the commander

“Finding my position untenable, shortly after 10

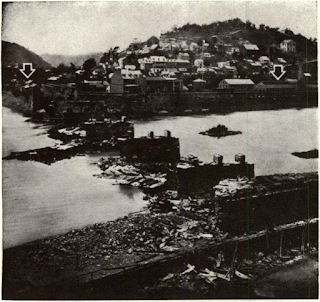

15.000 stand of arms, and burned the armory building

The arsenal was beyond hope of saving. Though the

above, and with a crash the second floor cascading

At the manufactory were two lines, for producing

Jubilant Maryland troops took 17,000 gun stocks

On May 7, , Colonel T. J. (Stonewall) Jackson

“Finding my position untenable, shortly after 10

15.000 stand of arms, and burned the armory building

The arsenal was beyond hope of saving. Though the

above, and with a crash the second floor cascading

At the manufactory were two lines, for producing

Jubilant Maryland troops took 17,000 gun stocks

On May 7, , Colonel T. J. (Stonewall) Jackson

Comments

Post a Comment