Crockett organized the pistol makers and on March

The firm organized by Crockett was styled Tucker,

Crockett now devoted his whole time to the project,

Crockett planned to set the works up as a major

pressment of the guns by the military. He states positively June 30, “We have several hundred on the way

Tucker, Sherrard & Company wanted the Board to

The Board replied, sending out Major George

We are now at work on the third hundred pistols and our

Crockett remarks on the low price the state was

Crockett persistently puts off the Board on the times

mount to $100. On September 24, , the remaining

Crockett again writes, on November 20, now weeks

The writer has devoted his whole time to the business since

Crockett furnishes some astonishing information concerning the manufacture of Colt revolvers, as it was

Colt’s pistols are not pure cast steel and scarcely a piece

We beg leave to assure the Board that out of, we hope,

By January 28 matters had not improved. Though

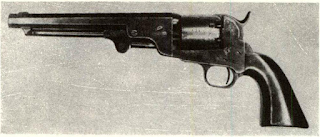

Six-shooters. We were shown the other day a beautiful

We learn that Col. Crockett has now 400 of these pistols

In an attempt to jack up the ante from the Board,

Possible cause for Crockett’s bringing the contract

Finis cannot be written to the story of the TuckerCrockett pistols. Analysis of the above testimony reveals

A. S. Clark, maker with Sherrard of the dragoonsize revolvers, seems to have worked with Crockett.

I was born in the town of Lancaster, Texas, in , and

A. S. Clark never left Lancaster to go into the Army and

In later years of my life, being related to him by marriage,

I became intimately acquainted with him and have often

It seems he was brought to Lancaster from Michigan, or

The firm organized by Crockett was styled Tucker,

Crockett now devoted his whole time to the project,

Crockett planned to set the works up as a major

pressment of the guns by the military. He states positively June 30, “We have several hundred on the way

Tucker, Sherrard & Company wanted the Board to

The Board replied, sending out Major George

We are now at work on the third hundred pistols and our

Crockett remarks on the low price the state was

Crockett persistently puts off the Board on the times

mount to $100. On September 24, , the remaining

Crockett again writes, on November 20, now weeks

The writer has devoted his whole time to the business since

Crockett furnishes some astonishing information concerning the manufacture of Colt revolvers, as it was

Colt’s pistols are not pure cast steel and scarcely a piece

We beg leave to assure the Board that out of, we hope,

By January 28 matters had not improved. Though

Six-shooters. We were shown the other day a beautiful

We learn that Col. Crockett has now 400 of these pistols

In an attempt to jack up the ante from the Board,

Possible cause for Crockett’s bringing the contract

Finis cannot be written to the story of the TuckerCrockett pistols. Analysis of the above testimony reveals

A. S. Clark, maker with Sherrard of the dragoonsize revolvers, seems to have worked with Crockett.

I was born in the town of Lancaster, Texas, in , and

A. S. Clark never left Lancaster to go into the Army and

In later years of my life, being related to him by marriage,

I became intimately acquainted with him and have often

It seems he was brought to Lancaster from Michigan, or

Comments

Post a Comment