One of the largest ordnance establishments in the

Enfield rifles were made and examples exist marked

Prior to evacuating New Orleans, Cook dallied with

The move to Athens caused a renegotiation, with

Four patterns of Enfields were made, all conforming very closely to the British original. An inspector had urged that Cook be provided with a set of gauges,

Cook barrels were of unusual construction, of

Shortage of skilled labor gave Cook many problems,

I have yet inspected . . . The establishment reflects

Burton wanted to buy the factory. Under his expanding authority, it was to come within his power

In February and March, Colonel Burton proposed

Francis Cook recovered control of his armory from

Enfield rifles were made and examples exist marked

Prior to evacuating New Orleans, Cook dallied with

The move to Athens caused a renegotiation, with

Four patterns of Enfields were made, all conforming very closely to the British original. An inspector had urged that Cook be provided with a set of gauges,

Cook barrels were of unusual construction, of

Shortage of skilled labor gave Cook many problems,

I have yet inspected . . . The establishment reflects

Burton wanted to buy the factory. Under his expanding authority, it was to come within his power

In February and March, Colonel Burton proposed

Francis Cook recovered control of his armory from

|

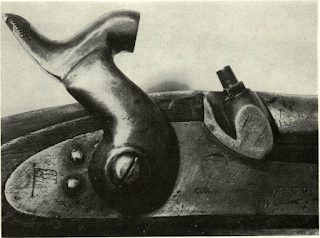

| Stars and Bars signed lockplate |

Comments

Post a Comment