Generically, the Deringer pistol, or “Derringer” as

In or ’43, the plant was relisted due to renumbering of that part of town, and became known

Deringer sporting guns, or defense pistols, included

The back action lock was adopted as standard. While

Big pistols, other than Government models, had

The variety of even the “genuine Derringer,” as

Genuine Deringer pistols of pocket size so far as is

In or ’43, the plant was relisted due to renumbering of that part of town, and became known

Deringer sporting guns, or defense pistols, included

|

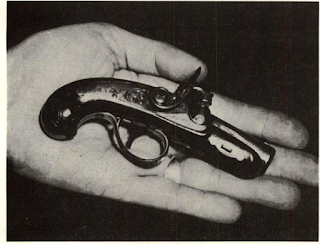

Small as the palm of his hand,

|

The back action lock was adopted as standard. While

Big pistols, other than Government models, had

The variety of even the “genuine Derringer,” as

Genuine Deringer pistols of pocket size so far as is

Comments

Post a Comment