The Virginia State Armory at the south end of Fifth

The move to refit the establishment as a manufacturing armory began stirring in February of . On the

Colt did not reply directly, at least he did not accept

Hartley was authorized to present a proposal of four

Second, Colt would contract exclusively with Virginia for a fixed length of time to make any of his arms

Hartley at once went to Richmond, and made a

Hartley; the water “can be used three times,” i.e., drive

After January 1, , Colt continued to be sanguine that some arrangement could be made with the

While Colt had adherents in the Capitol, and master

Adams and his assistants were engaged in this work

The move to refit the establishment as a manufacturing armory began stirring in February of . On the

Colt did not reply directly, at least he did not accept

Hartley was authorized to present a proposal of four

Second, Colt would contract exclusively with Virginia for a fixed length of time to make any of his arms

Hartley at once went to Richmond, and made a

|

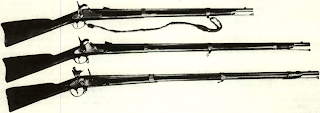

Richmond also assembled guns using captured and salvaged

|

After January 1, , Colt continued to be sanguine that some arrangement could be made with the

While Colt had adherents in the Capitol, and master

Adams and his assistants were engaged in this work

Comments

Post a Comment