Over the South, derringer suppliers had a brisk sales

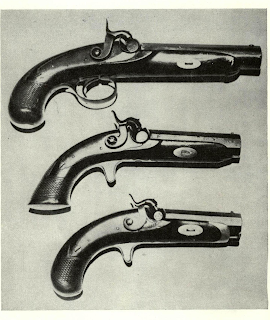

A handsome pair of G. Erichson, Houston, derringers in the Pugsley collection show the “Houston

screws than the plain ovals on an E. Schmidt, Houston,

Who actually made these pistols is still in doubt,

The details are exactly like their counterparts on a

indicates that up to the mid-century at least 95 per

Belgium in the old days apparentiy made a few of

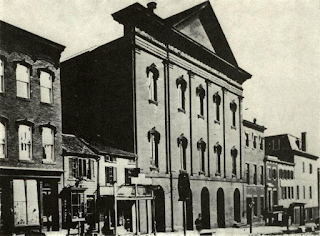

The tall man slumped forward, his head sagging

Below, the theater audience wondered if this was

To horse, then hooves clattering on the cobbles in

From the theater, Booth fled into Maryland. He

Today, Ford’s Theater is a museum, a sober monument to this black night in America’s growing up.

he uttered his cry as he jumped from the President’s

A handsome pair of G. Erichson, Houston, derringers in the Pugsley collection show the “Houston

screws than the plain ovals on an E. Schmidt, Houston,

Who actually made these pistols is still in doubt,

The details are exactly like their counterparts on a

indicates that up to the mid-century at least 95 per

Belgium in the old days apparentiy made a few of

|

| The assassin, John Wilkes Booth. The martyred President, Abraham Lincoln. |

|

| Derringer pistol used in the assassination of Lincoln, |

Below, the theater audience wondered if this was

To horse, then hooves clattering on the cobbles in

|

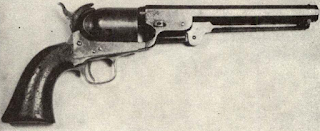

| The .44 caliber Colt pistol carried by Booth. |

|

| The .36 caliber Colt carried by Booth. |

From the theater, Booth fled into Maryland. He

Today, Ford’s Theater is a museum, a sober monument to this black night in America’s growing up.

he uttered his cry as he jumped from the President’s

Comments

Post a Comment