Hannibal Hamlin was appointed chairman of the

The subject is entirely too lengthy to do more than

Back in , the complaint was that the Ordnance

Associated with Senator Sumner was Senator Carl

The gross amount received during fiscal year ,

Two Acts related to the conditions of the sales. The

The Act clearly related to those arms, among other

While many of the complaints raised at the vast

was another law in effect more directly relating. As

On the close of the late War, in , the Government

“That the Secretary of War be, and he is hereby authorized and directed to cause to be sold, after offer at public

The Committee found in the wording of this Act,

The actual course pursued was far different, a

He claimed that France had charged the United

Surplus parts went into “sporterized” arms. Shown is controversial “forager’s shotgun” using Springfield Ml842 lock and

This area of discord surrounded the government

Seventeen shiploads of munitions went out alone on

Among the guns shipped to France were nine of the

The deal, “avoiding” complying with the directive

together with 240 of the special curved feed cases.

The arms sales investigation was concluded without

The minority view in the Senate was not fully in

. . . The Remingtons, after they had become known as

vigilant inquiry, have been early ascertained by the officers

The testimony develops other facts worthy of note in this

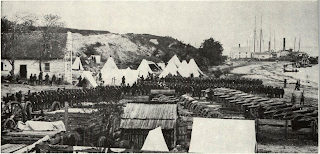

partly at pier No. 3, where steamships were loaded, known

by common report to have been chartered by the French

hands of one and the same party. This man (Starbuck) had

been charged with this business, and his receipts were

(This requirement for certificates was in conformity to the

But Garrison, though he doubtless testified truly

Cornelius K. Garrison did not enter into the arms

Garrison was to advance the money needed to pay

called for delivery of arms at Bordeaux by December

The French Government tried to abrogate the contract during the spring; the Chancellor of the Exchequer

A. B. Steinberger had turned over Enfields to Garrison, and from other buyers, as well as in his name, he

His reasoning was accepted by Colonel Crispin, who

As Garrison told Senator Carl Schurz under oath,

He then went on to speak of the Parrott rifled guns.

Garrison had chartered a steamer for shipping the

What Garrison had neglected to determine was that

pieces per battery, plus ammunition wagons, field

forges, and complete harness to hook up six or eight

horses for draught. There were additional saddles,

“valise” saddles, for the artillerymen to ride the horses,

the rolling mass of the 160 pieces of field artillery more

Smith Crosby & Company actually paid the Ordnance

The location of these cannon today is a mystery.

Resolved, That a select committee of seven be appointed toThe testimony and report of the committee proceedinvestigate all sales of Ordnance Stores made by the Government of the United States during the fiscal year ending the 30th of June, AD , to ascertain the persons to whom such sales were made, the circumstances under which they were made, the sums respectively paid by said purchasers to the United States, and the disposition made of the proceeds of such sales; and that said committee also enquire and report whether any member of the Senate, or any other American citizen, is or has been in communication or collusion with the government or authorities of any foreign power, or with any agent or officer thereof, in reference to the said matter; and, also, whether breech-loading muskets, or other muskets capable of being transformed into breech-loaders, have not been sold by the War Department in such large numbers as seriously to impair the defensive capacity of the country in time of War; and that the committee have the power to send for persons and papers; and that the investigation be conducted in public . .

The subject is entirely too lengthy to do more than

Back in , the complaint was that the Ordnance

Associated with Senator Sumner was Senator Carl

The gross amount received during fiscal year ,

Two Acts related to the conditions of the sales. The

The Act clearly related to those arms, among other

While many of the complaints raised at the vast

was another law in effect more directly relating. As

On the close of the late War, in , the Government

“That the Secretary of War be, and he is hereby authorized and directed to cause to be sold, after offer at public

The Committee found in the wording of this Act,

The actual course pursued was far different, a

He claimed that France had charged the United

Surplus parts went into “sporterized” arms. Shown is controversial “forager’s shotgun” using Springfield Ml842 lock and

This area of discord surrounded the government

Seventeen shiploads of munitions went out alone on

Among the guns shipped to France were nine of the

The deal, “avoiding” complying with the directive

together with 240 of the special curved feed cases.

The arms sales investigation was concluded without

The minority view in the Senate was not fully in

. . . The Remingtons, after they had become known as

vigilant inquiry, have been early ascertained by the officers

The testimony develops other facts worthy of note in this

partly at pier No. 3, where steamships were loaded, known

by common report to have been chartered by the French

hands of one and the same party. This man (Starbuck) had

been charged with this business, and his receipts were

(This requirement for certificates was in conformity to the

But Garrison, though he doubtless testified truly

Cornelius K. Garrison did not enter into the arms

Garrison was to advance the money needed to pay

called for delivery of arms at Bordeaux by December

The French Government tried to abrogate the contract during the spring; the Chancellor of the Exchequer

A. B. Steinberger had turned over Enfields to Garrison, and from other buyers, as well as in his name, he

His reasoning was accepted by Colonel Crispin, who

As Garrison told Senator Carl Schurz under oath,

He then went on to speak of the Parrott rifled guns.

Garrison had chartered a steamer for shipping the

What Garrison had neglected to determine was that

pieces per battery, plus ammunition wagons, field

forges, and complete harness to hook up six or eight

horses for draught. There were additional saddles,

“valise” saddles, for the artillerymen to ride the horses,

the rolling mass of the 160 pieces of field artillery more

Smith Crosby & Company actually paid the Ordnance

The location of these cannon today is a mystery.

Comments

Post a Comment