“You can have anything you want made in the gun

A full study was prepared by me of manufacturing

Meanwhile, we tried to mail a Navy Colt to Brescia.

France and taken secretly to England, where it was

Desperate, Val turned to me and I promised to get

To be sure that the manufacture of the pistol was

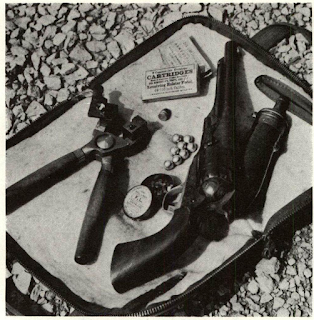

I received No. 1 of the Colt, the “Yank” and No. 13

Most of the changes were subtle; two are obvious.

I was later glad the grips were so different; at a

Characteristic of the Navy Arms pistols is the absence of the Colt safety pins on shoulders between the

It was almost ten months from my visit in the summer of that corrected the production error, to

Navy Arms also contracted for the Remington .44.

Witloe was too deeply committed in parts stock to

A full study was prepared by me of manufacturing

Meanwhile, we tried to mail a Navy Colt to Brescia.

France and taken secretly to England, where it was

Desperate, Val turned to me and I promised to get

To be sure that the manufacture of the pistol was

I received No. 1 of the Colt, the “Yank” and No. 13

Most of the changes were subtle; two are obvious.

I was later glad the grips were so different; at a

Characteristic of the Navy Arms pistols is the absence of the Colt safety pins on shoulders between the

It was almost ten months from my visit in the summer of that corrected the production error, to

Navy Arms also contracted for the Remington .44.

Witloe was too deeply committed in parts stock to

Comments

Post a Comment