The power launch which had brought us across the

The firm of Francis Bannerman Sons was a legend

Since that day in when I wandered into the

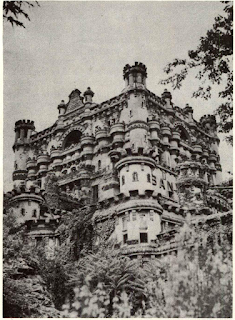

Bannerman bought the island in from one

On that Island, Francis Bannerman erected a

The potentially dangerous condition of the age-old

The breakwater (composed of thousands of .45-70

Inside the first floor of the main warehouse, we

We continued to probe. My gun-hunting instincts

To the rear on the first floor, Island caretakers had

On the second floor we discovered more interesting

I took the light and decided to pass to the highest

The castle roof was tarred, and sagging. One side

The third floor level had a southern exit to a castellated walkway that slanted down abruptly to ground

The second floor came in for another careful search.

Though Bannerman built for the ages, his castle has

El Presidente got a better deal with his cartridges

We walked outside again, and it was like walking

I had brought with me several old Bannerman catalogs, two dating back to and , and here in

“First American Breech-Loading Flint Lock Rifle

The founder of this fantastic arms business (which,

The business, managed by his father and later by

Young Frank had accompanied his father to the

Though Bannerman’s later catalogs intimated he

Not bothering to communicate the whole story to

The small-caliber cannon shells, 37mm or Hotchkiss

PISTOLS, HOLSTERS, POWDER TESTERS AND LOCKS

In these'days of modem weapons and factory-loaded cartridges* such a good,serv*

They are good,

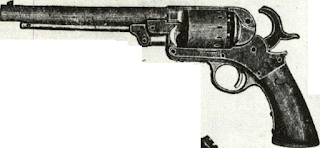

REVOLVERS AND PISTOLS.

Three trainloads of army goods bought by Scottish munitions king at turn of century included Rogers & Spencers for 25<t

Bannerman lived an adventurous life. The Mausers

does little or nothing to help their merchants trade in

Quickly, Bannerman took passage for Europe, entrained to the Balkan kingdom with his rifle and cartridges. He met the Serbian agent in Liege and gave

Dealer in second-hand goods, Bannerman often tried

By World War I Bannerman had grown to be the

Full-size illustration of the 60-Caliber Center-Fira

This Fencing

Socket and

NOT HIRING GENERALS.

Since the War tome of the private* have told with great

“ Who are those men working there ? ”

“ Them Is privates, sir, of Lee’s army.”

** Well, how do they worfc? ” ,

** Very fine, sir, first-rate worker*.”

** Who are these in the second groupJ

*• I sec you have a third squad, who are they ”

Them is colone's.”

“ Weil, what about the generals ? How dc they work ?"

Specialist at rebuilding long guns into short ones, Bannerman devoted a page of his catalog to short rifles which

largest house of its kind in the United States. A cooperative bidder with rival firms like W. Stokes Kirk

But Bannerman did turn out some unusual models

After World War I Bannerman’s firm kept active,

And through the years the Broadway store sold the

While Bannerman doesn’t have cases of muskets left,

The firm of Francis Bannerman Sons was a legend

Since that day in when I wandered into the

Bannerman bought the island in from one

On that Island, Francis Bannerman erected a

The potentially dangerous condition of the age-old

The breakwater (composed of thousands of .45-70

Inside the first floor of the main warehouse, we

We continued to probe. My gun-hunting instincts

To the rear on the first floor, Island caretakers had

On the second floor we discovered more interesting

I took the light and decided to pass to the highest

The castle roof was tarred, and sagging. One side

The third floor level had a southern exit to a castellated walkway that slanted down abruptly to ground

The second floor came in for another careful search.

Though Bannerman built for the ages, his castle has

El Presidente got a better deal with his cartridges

We walked outside again, and it was like walking

I had brought with me several old Bannerman catalogs, two dating back to and , and here in

“First American Breech-Loading Flint Lock Rifle

The founder of this fantastic arms business (which,

The business, managed by his father and later by

Young Frank had accompanied his father to the

Though Bannerman’s later catalogs intimated he

Not bothering to communicate the whole story to

The small-caliber cannon shells, 37mm or Hotchkiss

PISTOLS, HOLSTERS, POWDER TESTERS AND LOCKS

In these'days of modem weapons and factory-loaded cartridges* such a good,serv*

They are good,

REVOLVERS AND PISTOLS.

Three trainloads of army goods bought by Scottish munitions king at turn of century included Rogers & Spencers for 25<t

Bannerman lived an adventurous life. The Mausers

does little or nothing to help their merchants trade in

Quickly, Bannerman took passage for Europe, entrained to the Balkan kingdom with his rifle and cartridges. He met the Serbian agent in Liege and gave

Dealer in second-hand goods, Bannerman often tried

By World War I Bannerman had grown to be the

Full-size illustration of the 60-Caliber Center-Fira

This Fencing

Socket and

NOT HIRING GENERALS.

Since the War tome of the private* have told with great

“ Who are those men working there ? ”

“ Them Is privates, sir, of Lee’s army.”

** Well, how do they worfc? ” ,

** Very fine, sir, first-rate worker*.”

** Who are these in the second groupJ

*• I sec you have a third squad, who are they ”

Them is colone's.”

“ Weil, what about the generals ? How dc they work ?"

Specialist at rebuilding long guns into short ones, Bannerman devoted a page of his catalog to short rifles which

largest house of its kind in the United States. A cooperative bidder with rival firms like W. Stokes Kirk

But Bannerman did turn out some unusual models

After World War I Bannerman’s firm kept active,

And through the years the Broadway store sold the

While Bannerman doesn’t have cases of muskets left,

Iron Dog - TITIAN ART | TITIAN ART

ReplyDeleteIron Dog is welding titanium a 3D horse titanium for sale sculpture based on the famous titanium vs stainless steel apple watch Roman poem Yggdrasil, titanium water bottle and depicts the microtouch solo titanium warrior-headed eagle.