Dr. Paul Steiner, writing in Military Medicine, May,

Webb noted to Wadsworth that in his experience a case

“The bullet passed through the corner of my eye and

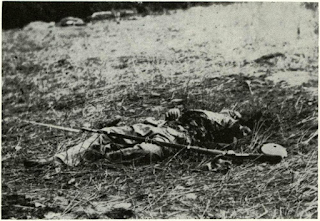

His colleague General Wadsworth fared less easily.

“I lifted his eyelids, but there was ‘no speculation in those eyes,’ ” Adams relates. “I felt his pulse, which

“The surgeons came Saurday night and examined

Webb noted to Wadsworth that in his experience a case

“The bullet passed through the corner of my eye and

His colleague General Wadsworth fared less easily.

“I lifted his eyelids, but there was ‘no speculation in those eyes,’ ” Adams relates. “I felt his pulse, which

“The surgeons came Saurday night and examined

Comments

Post a Comment