Even before organization of the Tredegar Works of

The South was not, as is often parroted by grade

“Great as was the loss of the ships,” wrote Admiral

A contract for artillery destined for Fortress Monroe

Archer and refund to Washington the money paid to

An enterprise of considerable size, the Tredegar

That a West Pointer should resign from the Army

When a visitor in September, , strolled through

Nearby, a whole new plant for making cast steel,

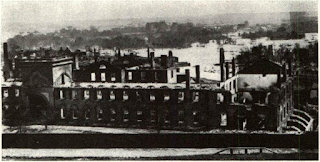

The record of the Tredegar in the years that fol-

The South was not, as is often parroted by grade

“Great as was the loss of the ships,” wrote Admiral

A contract for artillery destined for Fortress Monroe

An enterprise of considerable size, the Tredegar

That a West Pointer should resign from the Army

When a visitor in September, , strolled through

Nearby, a whole new plant for making cast steel,

The record of the Tredegar in the years that fol-

Comments

Post a Comment