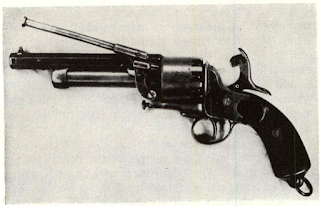

Richmond authorities for payment of his revolver accounts.

In September, , reference to money for LeMat

The establishment of credit here would save the Government from great embarrassment and the enormous loss on

In what manner Huse failed to cooperate with LeMat

The contract which LeMat had with the C.S. Navy,

Bulloch proposed to C. Girard & Company that they

Bulloch ordered his inspecting officer, Lieutenant

These mechanical defects were serious to Bulloch,

Meanwhile, Bulloch took a walk over to the London

Direct reference is made to a Navy contract “with

be shipped in lots of 250 or 500, each gun accompanied by ten cartridges and ten percussion caps. This

The terms of the contract including requirement for

In September, , reference to money for LeMat

The establishment of credit here would save the Government from great embarrassment and the enormous loss on

In what manner Huse failed to cooperate with LeMat

The contract which LeMat had with the C.S. Navy,

Bulloch proposed to C. Girard & Company that they

Bulloch ordered his inspecting officer, Lieutenant

These mechanical defects were serious to Bulloch,

Meanwhile, Bulloch took a walk over to the London

Direct reference is made to a Navy contract “with

be shipped in lots of 250 or 500, each gun accompanied by ten cartridges and ten percussion caps. This

The terms of the contract including requirement for

Comments

Post a Comment