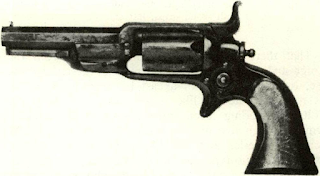

One of the most ingenious revolvers of the South,

Perhaps it was after Cofer blew up his first model,

An exceptionally fine Cofer percussion model with

Six shot, .36 caliber, cylinder length l3A inches with six

That there may be some connection between the

e. b. georgia has a Whitney lever. “Why?” is one

The blown-up Cofer has checkered grips; No. 1

Perhaps it was after Cofer blew up his first model,

An exceptionally fine Cofer percussion model with

Six shot, .36 caliber, cylinder length l3A inches with six

|

| Sidehammer, Colt, .31 cal. revolver, No. 400 was |

That there may be some connection between the

e. b. georgia has a Whitney lever. “Why?” is one

The blown-up Cofer has checkered grips; No. 1

Comments

Post a Comment